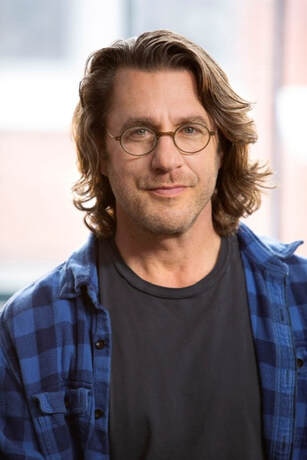

New York Times bestselling author BARRY EISLER spent three years in a covert position with the CIA's Directorate of Operations, then worked as a technology lawyer and start-up executive in Silicon Valley and Japan, earning his black belt at the Kodokan Judo Institute along the way. Eisler's award-winning thrillers have been included in numerous "best of" lists; have been translated into nearly twenty languages; and include the #1 bestseller THE DETACHMENT, LIVIA LONE, THE NIGHT TRADE, and THE KILLER COLLECTIVE. For more information, visit barryeisler.com. His new book, AMOK, is now available.

Dave Watson: Congratulations on AMOK. You take things in different directions this time, inside a character with family and with international events in countries Indonesia and Timor. What prompted this?

Barry Eisler: So it’s two things. One is Dox’s family situation, the other is this not very well-known war, Indonesia’s invasion and occupation of a neighboring country, East Timor, which was a Portuguese colony, there was a brief civil war, and then in 1975 Indonesia invaded and occupied the island for sixteen years, then finally the East Timorese won their independence in 1999. The book is set in 1991 when the war was hot. It’s a war not many Americans know about probably because America was not directly involved.

It was a really interesting conflict for so many reasons. One is the Indonesians should have known better. They were occupied by the Dutch all the way through World War II, then the Dutch were expelled, and what did they do? They invaded another country and tried doing the same thing that was done to them. There’s that saying that people don’t really hate bullying, they hate being bullied. Anyway, that was Indonesia’s war, and America and Australia backed the war. None of this is very well known in the States.

The reason I picked this as background for the book is, I wanted write an origin story. I had some notions about Dox, where he came from, what were some of his formative experiences and there are certain things that have come out about Dox in the books I’ve written. At one point he makes a joke about a palatial spread in his home in Abilene, and maybe it’s just because I like the song “Abilene,” so that’s a marker and I can’t change that, and I just started thinking about all the things that could have formed this guy we get to know present day, and I realized one of those things would be a conflict where he learns how the world really works.

I joke with my editor and my wife, Laura Rennert, who’s also my agent, I wrote a bildingsroman which is a novel of education, a German word, so for those of you who don’t know, it’s a coming-of-age story. I wanted to write about a naive guy who had some hard, searing experiences that forged the character we meet later on. The way I organically decided to do that was bookend the story at home in a town called Tuscola, a town of about 700 souls right next to Abilene, so not Abilene proper, but in Tuscola where Dox went to high school. I wanted to see him in Tuscola before and afterwards, to see how that conflict changed him. So, I came up with the structure working within parameters established in the earlier stories.

1991 was about the right year. I could have made it a little sooner, a little later, but there were some things that happened in Timor specifically., including an infamous massacre of something like 250 peacefully protesting Timorese at Santa Cruz cemetery by Indonesian troops that made sense in the story, so it was iterative.

What’s the fictional world I’m trying to create, and what is the real world I have to work with that lends itself to the story? Not that there’s anything wrong with changing reality; Quentin Tarantino did it masterfully in Inglourious Basterds, but that wasn’t the type of story I was trying to create. I could have had the Timorese turn the tables at the Santa Cruz Cemetery, but that’s not what happened.

DW: We meet Dox as a young man. I feel like we meet Dox and he’s a developing character. Would you say he’s in early adulthood then? He has a lot of years ahead of him, so we’re filling in the gaps. Is that what you were after?

BE: There’s an interesting question: what constitutes an origin story? Is it when his parents met? When he was a baby? There’s no one-size-fits-all answer to that question.

I’m looking for something that fundamentally made Dox what he is today. For me this goes all the way back to law school, I remember two concepts in Torts. So, somebody is texting while driving and hits you and breaks your leg. Now you sue that person for damages. There are causations that have to be met in order for it to work.

There’s “But for” causation, and then there’s proximate causation, a bit of a weird name, probably should be called “legal causation” or something. “But for” causation is just but for my existence, you wouldn’t have gotten hurt, so in that sense yes, I caused the accident. Legal/proximate causation is yes, I was texting, and that’s illegal. But what you wouldn’t do is say, “Barry, if you hadn’t gotten in that car, you wouldn’t have hit that person, and that’s enough to make you liable.”

Dox’s “but for” causation was American Cyclone, America’s clandestine effort to aid the Mujahadeen, known later less affectionately as Al Qaeda, in their guerilla war against the Soviets. It wasn’t like Dox was some neophyte when it came to war and clandestine conflicts. In my mind that was all the “but for” causation of the character, but there wasn’t something that happened to him that really made him the character we meet later on, and that’s what this story is about, the crucible that forged him.

DW: We meet him earlier. I remember him being this big, hulking iron-clad person set in his ways, self-directed, internal locus of control, whatever psychological aspects you want to project on him, but he wasn’t always that way, even, say, back in high school.

BE: Readers will recognize him, but it’s not like readers won’t recognize him twenty-seven years later in my third Rain book, Winner Take All.

When you think of yourself twenty years ago, it’s not like you were a completely different person you wouldn’t recognize. But there are things you that have changed: your outlook, your philosophy, your values have evolved. Hopefully I was able to depict something like that with Dox. It was a bit of challenge. Judging by the messages I’ve received, Dox is probably my most beloved character. People are really attached to this guy. So to write an origin story about someone people feel so invested in, you could definitely leave some people feeling disappointed.

There’s an example of that, the first Hannibal, so no disrespect to Thomas Harris, and I think they paid him $10 million to write that book, and I’ll admit I’d probably write anything for $10 million, so anyone who’s reading, you know how to reach me (laughs), but the truth is, artistically, common sensically, Hannibal shouldn’t have gotten an origin story. He’s a force. He even says that to Clarice in the book or the movie: “You can’t explain me. You can’t examine me. I’m a hurricane of evil.” Not that it was a bad book; it just wasn’t a good idea to give him an origin story. But for Dox I don’t think he’s a hurricane or other unexplainable thing. There must be essential explanations for the characteristics we get to know later on.

I gave a lot of thought to that, and so far from reader reactions, I feel really pleased I was able to create a story that causes this reaction. There’s a screenwriting guru named Robert McKee who I think is terrific.

DW: His book Story.

BE: That’s his first. As it happens, I’m reading his latest, Action. I’ve gone to a couple of his seminars and I think he’s great. Some people who don’t really understand him or just want to be critical say he’s just giving you a formula. If there’s one thing I’d change about the Internet, it would be to make people familiarize themselves with things before criticizing. You still may want to criticize, but your criticism would be of greater value if you knew what you were talking about. McKee is at pains to say, “I’m not telling you you have to do anything. I’m teaching you about principles, things that if you do them, they will work.”

Another saying is that rules are meant to be broken. I hate that saying. It’s a good tagline for the Jason Statham movie The Transporter, but in fact it doesn’t make sense. Anyone can break a rule; a monkey can break a rule, a neophyte, a child, a barbarian, you can break the rule but you won’t get good results. What you want to do is learn the rules so well that you can bend them to your purpose. That’s the goal: to learn how to bend the rules to your purpose.

McKee also talks about what makes a great surprise ending, and I thought this was a really interesting rubric. He said a great surprise ending has your mind racing back and seeing the same things in this new context, and the feeling in the face of a great surprise of “Oh my God!” like at the end of M. Night Shyamalan’s The Sixth Sense, or with, “Luke, I am your father…” or whatever. You have this moment of, “Oh my God! Of course!” You didn’t see it right in front of you, but it all makes sense. It’s surprising, but it’s not astonishing.

Again, breaking the rules, it’s easy. You’re not going to have Santa Claus show up in a story that’s not about Santa Claus, that would be very surprising, but not a satisfying surprise, dramatically. With all that, I don’t want you to be surprised and get ahead of the story. If you don’t know Dox it’ll just be a really good story, I hope. If you do know Dox, you’ll say, “Of course, this has to be his background!”

DW: Yes, I agree. You tie the events and ideas together; it’s not like it goes to a place and does this, then he goes somewhere else and does this. For endings, The Usual Suspects comes to mind.

BE: I love that movie.

DW: There’s one shot, maybe two or three seconds long where he’s looking at the wall. At the end we go racing back to that shot.

BE: And at the end Chazz Palmintieri looks at the board and there are pictures of the choir, the barber shop quartet, the Kobayashi coffee mug and you say, “Oh my God, it was right in front of me that whole time!”

DW: That movie came out twenty-seven years ago and many people remember the first time they saw that.

BE: It holds up. Great movie.

DW: You balance backstory with the present. When we meet people, we notice everything on the surface, then we spend time with them. Do you see people as half-revealing, half-suppressing agendas and values, as a human being and a writer?

BE: That’s a really interesting question. So another thing I learned from McKee to be more conscious of is text and subtext in dialogue. Text is just what’s said and subtext is what’s meant. Generally speaking, the greater the gap between text and subtext, between what’s being said and what’s meant, the more the dialogue will crackle, the more it will engage you. So, like most principles that express themselves in one relatively narrow set of circumstances, you can see the text-subtext dichotomy in many other settings and contexts besides just story dialogue. Really, it works for almost everything among the humans. I really like to use that term, by the way, because it’s almost like I’m not among humans, I can observe them and be a more dispassionate observer even though I’m of course talking about myself as well.

One of the notions I like is that as humans we tell ourselves we think we know why we do things, while really, except for minor things like I get a glass of water because I’m thirsty, we tend to be not that in touch with our true motivations. In fact, we typically have some sort of subterranean emotional motivation to take an action, and then, in addition to being emotionally motivated, we’re also emotionally motivated to deny that we’re emotionally motivated. We’d rather to retrofit a logical facade to justify actions after the fact.

If you ask people why they do or did things, they’ll give you the answer but it isn’t usually the right answer. In Japan there’s a duality, honne and tatamae. Honne means the real truth, while tatamae is the facade of truth. It’s not that tatamae is false, it’s just not the whole truth. If you ask a cop why he does what he does, he’ll say to serve and protect. I’m not saying that’s false. But there’s something more individual beneath the surface, something more that a person doesn’t want to admit, even to his or herself. That kind of dichotomy interests me a lot. I think a writer has to understand that dichotomy.

And the better you understand it, the more effectively you can work with the other humans. You’ll write about them better and understand them better. What makes humans tick is not on the surface, it’s not what humans tell or show each other. It’s not Instagram profiles; that’s what we want the world to see, that’s just the surface. But how much can you know about the ocean by knowing just what you can see on the surface?

I just listened to a terrific new book which I highly recommend to anyone interested in movies—Quentin Tarantino’s Cinema Speculation. He narrates only the first and last chapters and is so passionate about movies that even though the other narrator is good, I wish Tarantino had read the whole thing himself. I bring it up because Quentin talks about Deliverance, which he saw when he was eleven. He discusses Burt Reynolds’s character, Louis, and how Louis presents himself. It’s not that Louis is full of shit, it’s not that this image he’s trying to present to the world is false, it’s that there’s a lot more going on beneath the surface than Louis is letting on, maybe even to himself. That kind of stuff is what interests me the most about people and character and stories, the subterranean.

The unconscious is what drives what we do, not what we’re aware of. If you’re not in touch with that, it’s probably going to be a challenge to create realistic, compelling characters for the page. So this dichotomy is something I definitely use in trying to get along with and understand other humans, and to create compelling characters.

DW: There’s a reason that story is set on the river. You also start with a detective and reporter right in the middle of the action. You’re revisiting a scene. They see things differently. I just read Heat 2 by Michael Mann and Meg Gardiner.

BE: I love that movie. That book is on deck after East of Eden.

DW: Heat 2 goes into backstory, but we still don’t know what makes Chris Shiherlis tick all the way. Heat is another movie from twenty-seven years ago.

BE: Tarantino talks about the antecedents of the characters. Neal McCauley is probably the best screen version of Parker, Donald Westlake’s character.

DW: I recall you reading Reporter by Seymour Hersh a while back. You seem plugged into the real world though you write fiction, similar to the recently deceased Andrew Vachss. Who are some of the best nonfiction and fiction writers working today?

BE: Well, Vachss was the best. Anytime someone compares me to him it’s an honor. It’s funny, for whatever reason it was never a a plan. I really like to set my stories in nonfictional settings where I’ll go somewhere and I write about it. If I change something I call it out in an Author’s Note at the end so readers trust me.

It’s true for physical setting and also true for backstory. I know the technology in The God’s Eye View is out there, and I want people to know that I’m setting this fiction in a nonfictional world. I guess it’s a little odd that even though I do that organically, I don’t notice it in other people’s books.

There’s a wonderful mystery from decades ago called The Tears of Autumn by Charles McCarry. It’s a novel with the Kennedy assassination as the backdrop. It fit so well with historical events that I came away thinking, “Wow, that’s so compelling that must be the true story of what happened.” I don’t know how much fiction McCarry mixed in with all the fact he was clearly using.

I mentioned East of Eden, and the narrator, Richard Poe, is terrific, with a voice like Frank Muller, an extraordinarily gifted narrator who did everyone from Stephen King to Moby Dick to Cormac McCarthy to Elmore Leonard. He was so good.

The whole first chapter of East of Eden is in a way a high-wire act. Elmore Leonard had his rules for writers and one was, “Don’t start with the weather.” But like with all rules, they’re meant to be bent: if you can write a compelling scene about the weather, if it makes the reader eager to go on to the next sentence, then write whatever you want. It’s not easy drawing people in talking about the weather, but John Steinbeck spends the whole first chapter describing the entire Salinas landscape: the dirt, the colors, the climate, the rain, the dry, the harvest, then he starts weaving people in because it’s multi-generational, but the amount of real stuff, stories of town names, the Spaniards naming the towns, so it’s always San this and San that, what you can tell about the towns themselves, how they’re named “Lost purse” and things like that; there must have been a story behind the name of that town for how much he devotes to it. You could almost be reading something nonfictional given the amount of information–I love it!

For his movies, Michael Mann really immerses himself in this stuff. He works with criminals. The Jericho Mile, which played on ABC over forty years ago, was shot in a real prison. Sometimes my wife and agent Laura Rennert calls me a method writer: I go to places and walk in people’s footsteps. I really like that process and think it produces better results. Michael Mann is a great filmmaker and storyteller, but I have a feeling Meg Gardiner did a lot of the heavy lifting on Heat 2. She’s great.

DW: In an interview she said that she and Michael discussed every word in that book. It’s a big book, a big roast beef or veggie sandwich you don’t want to end.

BE: I just finished a book on acting by Stella Adler. I’m always interested in the way, if a principle expresses itself a certain way in one realm, if it’s a sound principle, you’ll see it expressed in other realms, too. I thought, “I’ll learn some things about acting, I know a little about novel writing, screen and television writing, directing, mostly through MasterClass and BBC Maestro with great directors like James Cameron. So I read Adler’s book.

No disrespect to Adler, but there were a lot political glittering generalities and I thought, you have to put more thought into it than just that, your point is too broad. We’re all narcissists, it comes with being human and the packaging, and maybe actors are more narcissistic than most, but if your opinion is giving you pleasure, you should reexamine it and figure out where the opinion is really coming from.

But with regard to the craft, it’s a good book. One of the things I learned, one of the principles, was specificity. Specificity is compelling. If you look at the opening of Ken Follett’s The Key to Rebecca--which is as good an opening as any ever written, and when I teach writing I use it as about the best example ever of how to seduce readers into a story—he doesn’t use the word desert for at least a few paragraphs, but he’s implying it, and giving you some closeup shots of rivulets of sand going down a hill from the camel’s hooves, that sort of thing. That sort of specificity can really bring a scene to life.

Stella Adler talks about how specificity helps actors and how it helps them inhabit and convey the roles they’re playing, and that made perfect sense to me as a writer.

DW: And it seems that if you’re going to operate in a genre, you’d better operate on principles. McCarry’s book came out eleven years after the JFK assassination. Do you feel like we have to give some historical events some time for us to see them more clearly? I bet you’ve seen Peter Weir’s 1983 film The Year of Living Dangerously set in Indonesia under Sukarno in 1960, and your book is set thirty-one years later in Indonesia-occupied East Timor.

BE: Yes, and it’s not just recency, it’s more like proximity. Proximity can be a lot of different things, including your own in-group, your own society. If it’s too close, people will resist it, which is why allegory can work so well.

This goes back to how humans are wired. We have built-in defense mechanisms. If you try to present something too directly, if you’re flattering someone, that can work great—they want to hear that stuff, but if what you’re saying is not flattering, they will tend to resist, and one way to get past those defenses is one, to make something remote in time because in general people have less attachment to events from the remote past. You can also set something in a different society, like the animals in Orwell’s Animal Farm, or you can set it in space, etc., and the distance helps the themes reach people who would otherwise resist.

If you think of James Cameron’s Avatar sequel, what is it about? Imperialism, colonialism. If you present something directly to an American audience that suggests America is an imperial power, there’s inherent resistance. The more recent and central that thing is to America, the more resistance you’ll get. Avatar moved this themes into the future, to another planet.

If you think about, there are jokes about the Lincoln assassination, “What else didn’t you like about the play, Mrs. Lincoln?” If you told that the day after, it wouldn’t have gone over well. So the closer we are to an event, the harder it is to use our reason to assess the event with a person, the circumstances, whatever, so yes, distance can be very important, even critical.

DW: I taught English in South Korea for a year and went to Hiroshima on August 6, 1995. It was a very moving ceremony with some high officials speaking about nuclear non-proliferation. When I got back to Korea, students picked me up at the airport and said, “Well, they can’t really say much about war, can they?”

BE: There’s an expression I came across not long ago, “The axe forgets; the tree remembers.” I’m a Japanophile—I lived there for four years and speak Japanese, and I think there are so many wonderful things about Japanese society. But of course the country is made of humans, and Japan has a terrible, colonial history that the country has a tendency to memory-hole. Not throwing stones here; as an American, that would be beyond hypocritical. But it’s understandable that Koreans remember being colonized by Japan in a way the Japanese tend to overlook. The axe forgets; the tree remembers.

I’ll say this, though. I wish more Americans were aware of what those bombs did in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and there are photos on the Internet for anyone who wants to know. I’m still struck by the way people dismiss the risks of nuclear war in Ukraine and across the board. If people understood how close we’ve repeatedly come…all people know about is the Cuban Missile Crisis, if they’ve even heard of that. In fact there have been numerous unbelievable near-misses, or as George Carlin would say, near-hits. Humans should not have these guns. We’re playing Russian Roulette, and one day the bullet’s going to be in the chamber. You play that game long enough, the gun is going to go off. It’s a miracle it hasn’t happened in seventy-plus years.

I wish people would look at those photos; they’d be a little less sanguine. Wars happen without people wanting them to, as Barbara Tuchman observed in her book about World War I The March of Folly. What’s happening now is a lot more like World War I, or like the Cuban Missile Crisis combined with World War I. So with regard to Hiroshima and Nagasaki, people say, “Well, we did what we had to do to win.” They’re too quick to dismiss what happened: a quarter of a million people were killed. Innocent people, children, babies had their skin melted off their bodies. They died excruciating deaths. Get your mind around some of that before you blithely dismiss the possibility of it happening again—or worse.

Regarding the American nuclear codes, the nomenclature is, “The president carries the football.” I’m fascinated by this nomenclature, as though it’s a game. In fact, there’s a command-and-control structure most people don’t know about. Any president can end the world on a whim. There’s nothing between the president giving the order and the order being carried out. The philosophy is, “We have to launch our missiles, there’s no time, the Russians or Chinese will take our missile out if we wait, so the president’s whim goes straight to the silos.

Someone, I don’t remember who, said what the president should have to do, the president shouldn’t just be given the access codes by some guy holding a briefcase. The guy with the codes should have them planted in his chest, and the president should be given a knife with which he has to carve out the codes out before launching missiles and obliterating millions of humans.

I think that’s a good idea because if you’re not willing to do it yourself, you shouldn’t be willing to do it to anybody. Obliterating millions of humans shouldn’t be antiseptic and easy. It should be disgusting and hard.

DW: Reading Bob Woodward’s book from a few years ago. We came dangerously close to nuclear disaster.

BE: You can Google how close we’ve repeatedly come to nuclear war, whether deliberately or by dumb accident, and it’ll make your hair stand on end.

DW: Greg Palast does his own investigative work on this. Eric Schlosser who wrote Fast Food Nation wrote a great book about how lax and faulty our security is around nuclear reactors. What’s next?

BE: I’ve written a couple things, one for television and another for feature, neither of which is yet produced. It’d be nice to see if that could happen because I’ve spent a lot of time learning how to write for screen and television. It’s a different kind of writing though of course there’s overlap, too.

I could go on and on about how different it is, but the gist is this: if you can’t present it on the screen, it doesn’t belong in the screenplay. There are exceptions, but in general if you’re writing for the screen you can’t say, “It was Tuesday morning and Bob was hungry. What would the actor do? Make a face? How do I know Bob was hungry?

DW: It has to be visual or strike an image in the mind.

BE: Exactly. You have to be able to act it, say it, present it on the screen. So sure, there are similarities, but you have to understand the differences, too. Which is another principle I like. There’s a self-defense guru I’ve followed for decades named Marc MacYoung whose book, Cheap Shots, Ambushes, and Other Lessons, terrific book, writer, and thinker! And Marc talks about how some people approach stick fighting and sword fighting. They say, “I get it, the physics are the same, the angles are the same, and Marc says, “Yeah, there are similarities—and the differences will get you killed!”

DW: Details matter.

BE: They do. Here’s something interesting for anyone trying to learn a new craft.

I’ve played around with martial arts, I’ve gotten competent in a second language, and I’ve learned writing, and there seem to be three levels of learning any craft. They’re not as clear-cut as all this, but for discussion purposes, the three levels are: theory, drills, and free practice.

With a language, theory is studying the grammar. With drills you’re implementing the grammar and learning vocabulary in a constrained, repetitive way. Then there’s free practice where you’re using the things you’ve learned in conversation.

With martial arts, to use another example, I’ve read books on takedowns and strangles and armbars. That’s theory. Then you can drill those techniques repetitively with a cooperative partner—that’s drills. And then sparring or actual fighting, which is free practice.

Learning to write is the same thing. Recently I read a fantastic book by K.M. Weiland on character arcs. Great example of theory. I should add here: another thoughtless expression some people are attached to, like “Rules are made to be broken,” is, “You can’t teach art.” That’s true but misleading. Nobody should be trying to teach art, but they should be teaching craft. You can’t be an artist without learning the craft. And theory is part of the craft. It’s not enough—you need the drills and the sparring, too—but it’s part of learning.

DW: That’s why there are Robert McKees and Michael Wiese Productions’ books.

BE: Yes, read the books for the theory. And what are the drills? The drills are to watch movies and read novels like a writer. Don’t get distracted by the emotions being conjured, even if you have to watch or read multiple times to habituate. But get past the emotion so you can analytically ask, “Why does this work so well?” Or conversely, “Why does this suck so much?” And, “How would I make it better?” Those are drills. And free practice is to work on your manuscript or screenplay. I’ve noticed all three of those levels in every craft I’ve ever tried to learn.

Anyway, so I’m working on some film stuff and on a new novel. People have been asking about a Rain prequel I have planned, but haven’t yet written. Maybe where Rain and Dox meet in Afghanistan, but I don’t feel competent to go there yet.

DW: That’s a big can of worms, existentially.

BE: I like to travel to these places and that’s a hard one to go to.

DW: You’ll go when you’re ready. What is your current favorite cinematic moment?

BE: Oh, that’s a hard question. Can I give you two?

DW: Of course you can.

BE: One’s old and one’s new. For no particular reason, my wife and I just re-watched Speed from a while ago, Graham Yost wrote it. That movie holds up perfectly! It’s fantastic, does so many things well, even when it goes over the top because it earns it—more delible moments than I can count.

A more recent one, a quieter but no less effective one, called Watcher, by a first-time director, or at least her first feature—Chloe Okuno.

DW: It’s her first feature, I believe, and made many best lists.

BE: What she did was make you feel the character’s paranoia as if you feel it yourself, and that took some real craft. Very interesting to watch and to ask, “What is Okuno doing that’s making me feel this way?"

Which is, of course, a drill.

Clip: Speed

Watcher

Founder and editor of Movies Matter, Dave Watson is a writer and educator in Madison, WI.