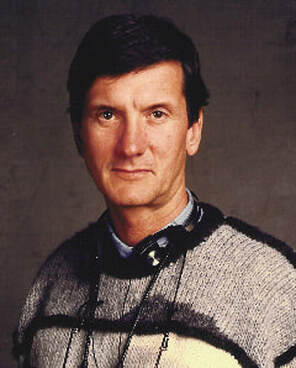

JOHN BADHAM has directed more than thirty-nine feature-length productions and many television shows over a career that has earned his projects Academy Award nominations, and international box office success. In 1977, he guided a then-unknown Travolta to worldwide fame with Saturday Night Fever, a cultural milestone that launched the disco era and went on to become one of the top-grossing films of all time. Other films Badham has helmed include Blue Thunder, WarGames, Point of No Return, Short Circuit, Bird On A Wire, Stakeout, Whose Life Is It Anyway?, and the stylized Dracula.

Badham is also a prominent television producer and director. He served as an executive producer for the Steven Bochco drama Blind Justice and directed several episodes. He has directed episodes for Siren, Supernatural, The Shield, Just Legal, The Jack Bull, Obsessed, and The Streets of San Francisco, and received two Emmy nominations for his work on the ‘70s series The Senator and The Law. His telefilm Floating Away, starring Roseanna Arquette, won a Prism award for its portrayal of alcohol abuse. He is Professor of Media Arts at The Dodge School of Film and Media, Chapman University. John's new book, ON DIRECTING - 2ND EDITION: NOTES FROM THE SET OF SATURDAY NIGHT FEVER, WARGAMES, AND MORE, is now available.

Order John's book here.

Dave Watson: John, you helped me launch Movies Matter almost seven years ago—thanks much! What's new with you since then? Seems like you're working up a storm.

John Badham: A lot has changed. For one thing, the change to digital became a revolution. Every television show is shooting digitally now. Though there are plenty of theatrical films that are still shot on film, digital has become the lingua franca of the entertainment business.

Second, the chasm between motion pictures and TV got narrower and narrower to the point that it disappeared altogether. We saw Universal just put up its own streaming version of Spike Lee’s new film Da 5 Bloods. This is following a decades-long battle with theater owners.

Even the Motion Picture Academy has changed its rules to allow films that ran exclusively on streaming media, not in the movie theater, to be eligible for Academy Awards. That’s a big change.

DW: And didn’t some studio executives predict the end of people going to movies, and correct me if I’m wrong, with the advent of VCRs in the late ‘70s?

JB: And there have been similar predictions since the advent of TV. In California in the 60’s, voters passed Proposition 15 outlawing cable TV. And the only cable TV was a tiny operation in Santa Monica called the Z Channel that ran recent movies. A few years later, the California Supreme Court overturned this law.

DW: Congratulations on a second edition of a great book. What's new this time?

JB: The biggest change is there’s a whole section on how to survive streaming TV as a director. In feature films, a director is near the top of the food chain. In the case of a television or streaming production, the biggest difference is a director sinks down lower in the hierarchy.

As a feature film director, you have a strong say in every step of the creative process: from script to casting, how the film is shot and edited, etc. But, in TV and most streaming media, much of this is done without you. The script is written, the roles are cast, the look of the film is pre-determined, and all this before you show up to work. In movies, you are, if not the boss, pretty damn close to it. With streaming, they barely put up with you. It’s like a Kafka novel. After you’re done shooting an episode, it goes to the editor, you get four days to work on it, then it’s out of your hands forever. It goes to the producers, who work on it, then to the studio, then to the network, who often change everything.

If directing is your calling, it’s important you understand the different ecosystems. My book explains how to navigate the politics of this new streaming world. Young directors, like the students I teach at Chapman University, have to learn that they don’t have the same power in episodic television as they might be used to on their student film set. As a first-time director to a series, you need to know how to work your way through these limitations without getting a bad rep for insisting on being “too creative”.

It has often happened that a director does a great job on a pilot for a series and it gets sold. But that director never gets asked to shoot any more episodes. The producers may say, “No, we don’t talk to them anymore.” That might be because the director stood up for themselves more than producers wanted.

DW: Which might be hard, because from the outside, they produced and created great work. You would also have to be very open to ideas and have to work with all kinds of people through that process. In our first interview, I recall you quoting your dear friend John Frankenheimer saying, "I never learned anything about directing by ‘not directing.’" You strike me as open to learning all the time. What are some big lessons you've recently learned you could pass on to young filmmakers today?

JB: You have to keep working. John’s quote certainly holds true. When I’m directing, I’m solving problems, which are in everything we do: every show, scene, every shot. Richard Dreyfuss remarked once, that even much of acting is problem-solving.

DW: You poll wisdom from a broad range of sources in your book, from directors to actors to other roles on a film set. Do you have to balance outside ideas with your vision?

JB: I want ideas. I think anybody who doesn’t want ideas is ignoring the wealth of talent around them. Good ideas come from everywhere: camera people, actors, prop people, makeup, etc. There often is a germ of a good idea in one that may sound silly on the surface.

DW: Does that include the writer's vision when working on a series?

JB: You better be paying attention to the writer’s vision. It’s their script and their hard work that got us to this point. When I go in as a director, I do my best to understand what the writer has in mind. If I don’t understand that, I’ll make a mess of their script. If I have any suggestions for changes, I’ll go right to them and we work it out.

Remember, the writers are almost always the producers. Many shows have fourteen producers; twelve of them are writers, on staff all the time. If you’re the director, you’re there for six to eight weeks, and then you’re gone. Who’s going to win in this environment?

DW: And this seems to be the case from Mr. Mercedes with AT&T and The Audience Network to The Outsider at HBO—you see the same names in the credits. We noted that your films mix genres. As streaming is still surging alongside theaters, do you see shows and series as mixing genres?

JB: There are so many different kinds of genres. There are some sci-fi shows that are also comedies. I’ve directed the sci-fi Siren, which is set in a realistic New England village, and it has mermaids that transform into creatures that walk on two legs. Mermaids are often treated as comedic, certainly fanciful. But Siren is filmed in a very documentary style. The great show The Office is a comedy faux documentary. Anything is possible if it’s a good story.

DW: Your films also celebrated everyday people, thinking of Richard Dreyfuss, Roy Scheider, Ally Sheedy, and Matthew Broderick. Though superheroes appear to dominate the market for some people, do you think there's still appeal for that type of hero?

JB: People like to relate to characters in stories; it’s fun! Now, younger audiences may tune in to superheroes, but there’s always an audience saying, “This is us” when they see real people. If they can relate to a character, they may not be a hero, but they’re fallible. I was watching Homeland, and Claire Danes, who’s wonderful in it, but her character is so terribly fallible. When she beds the villain, we say, “No, don’t do that!” We like characters often because of their fallibility. With the show Succession, there’s hardly a likable character; everyone’s a mess. And we love it.

DW: Your career has spanned five decades as of next year. What are some of the biggest industry changes you've noticed? I realize this is a loaded question, and we talked about this a little.

JB: A big change over the last seven years is the explosion of streaming outlets. It’s not just the same old four networks that depend on advertisers for their revenues.

Two, we’ve gone from film to digital media. Three, Big studios are now run as a gig economy instead of long-term contracts. When I started in the mailroom at Universal, everyone, even me, was on contract. Now, employment deals are one job at a time.

DW: It sounds shaky though, and if it feels different, that ties back to why we go to the movies.

JB: Sometimes I’ll flashback to when directors like King Vidor or Billy Wilder or John Ford were in their heyday. Everyone was under contract, and you stayed at a studio for years. Now, you wonder if you go out to lunch, will they need you in the afternoon?

Another big change with series nowadays is that there’s a new job: producer-director. They are an experienced director who is there every day, working with this week’s director to supervise them and teach them all the dos and don’ts of that particular show. That producer/director is there to protect the ‘brand’ that is their show.

You often hear producers say is, “We don’t like surprises.” They’re protecting the brand that is their show. It reminds me of the time I was shooting in a McDonald’s in their kitchen, lining up a shot. On the wall was a blow-up of a Big Mac. It was up there so that anyone, even a brand-new employee, could assemble a perfect Big Mac. TV shows are kind of like that, the same every time. With a Big Mac, you can’t move the pickles to a different spot, put the cheese under the burger or leave the lettuce out. It’s the ‘pickle rule’ in directing. Don’t mess with the brand.

DW: As it is a brand, you know what you’re getting.

JB: Whether you’re in Tokyo or in California.

DW: I was in Tokyo as a kid, and I went to a McDonalds.

JB: Of course you did!

DW: I knew what I was getting. Finally, do you have a favorite cinematic moment? A shot, a scene—one you saw growing up or recently—that stands out?

JB: Oh, I’d have to say Once Upon a Time in the West, the opening ten minutes. I still watch it to this day. It’s a mystery where we have to puzzle out this wonderfully weird story unfolding before us. What’s going on we ask. We meet some of the baddest guys who were ever in Westerns. Charles Bronson, Jack Elam, Woody Strode waiting, waiting, waiting at a god forsaken train station out in the desert ? Why are these guys here? What do they want?

What happens is pure cinema. Me trying to explain it is like trying to explain Beethoven’s Fifth. You just have to hear it, or in this case, to see it. The ending of the sequence is a mind blower and one of the best openings to a movie ever!

Clip: Once Upon a Time in the West

Badham is also a prominent television producer and director. He served as an executive producer for the Steven Bochco drama Blind Justice and directed several episodes. He has directed episodes for Siren, Supernatural, The Shield, Just Legal, The Jack Bull, Obsessed, and The Streets of San Francisco, and received two Emmy nominations for his work on the ‘70s series The Senator and The Law. His telefilm Floating Away, starring Roseanna Arquette, won a Prism award for its portrayal of alcohol abuse. He is Professor of Media Arts at The Dodge School of Film and Media, Chapman University. John's new book, ON DIRECTING - 2ND EDITION: NOTES FROM THE SET OF SATURDAY NIGHT FEVER, WARGAMES, AND MORE, is now available.

Order John's book here.

Dave Watson: John, you helped me launch Movies Matter almost seven years ago—thanks much! What's new with you since then? Seems like you're working up a storm.

John Badham: A lot has changed. For one thing, the change to digital became a revolution. Every television show is shooting digitally now. Though there are plenty of theatrical films that are still shot on film, digital has become the lingua franca of the entertainment business.

Second, the chasm between motion pictures and TV got narrower and narrower to the point that it disappeared altogether. We saw Universal just put up its own streaming version of Spike Lee’s new film Da 5 Bloods. This is following a decades-long battle with theater owners.

Even the Motion Picture Academy has changed its rules to allow films that ran exclusively on streaming media, not in the movie theater, to be eligible for Academy Awards. That’s a big change.

DW: And didn’t some studio executives predict the end of people going to movies, and correct me if I’m wrong, with the advent of VCRs in the late ‘70s?

JB: And there have been similar predictions since the advent of TV. In California in the 60’s, voters passed Proposition 15 outlawing cable TV. And the only cable TV was a tiny operation in Santa Monica called the Z Channel that ran recent movies. A few years later, the California Supreme Court overturned this law.

DW: Congratulations on a second edition of a great book. What's new this time?

JB: The biggest change is there’s a whole section on how to survive streaming TV as a director. In feature films, a director is near the top of the food chain. In the case of a television or streaming production, the biggest difference is a director sinks down lower in the hierarchy.

As a feature film director, you have a strong say in every step of the creative process: from script to casting, how the film is shot and edited, etc. But, in TV and most streaming media, much of this is done without you. The script is written, the roles are cast, the look of the film is pre-determined, and all this before you show up to work. In movies, you are, if not the boss, pretty damn close to it. With streaming, they barely put up with you. It’s like a Kafka novel. After you’re done shooting an episode, it goes to the editor, you get four days to work on it, then it’s out of your hands forever. It goes to the producers, who work on it, then to the studio, then to the network, who often change everything.

If directing is your calling, it’s important you understand the different ecosystems. My book explains how to navigate the politics of this new streaming world. Young directors, like the students I teach at Chapman University, have to learn that they don’t have the same power in episodic television as they might be used to on their student film set. As a first-time director to a series, you need to know how to work your way through these limitations without getting a bad rep for insisting on being “too creative”.

It has often happened that a director does a great job on a pilot for a series and it gets sold. But that director never gets asked to shoot any more episodes. The producers may say, “No, we don’t talk to them anymore.” That might be because the director stood up for themselves more than producers wanted.

DW: Which might be hard, because from the outside, they produced and created great work. You would also have to be very open to ideas and have to work with all kinds of people through that process. In our first interview, I recall you quoting your dear friend John Frankenheimer saying, "I never learned anything about directing by ‘not directing.’" You strike me as open to learning all the time. What are some big lessons you've recently learned you could pass on to young filmmakers today?

JB: You have to keep working. John’s quote certainly holds true. When I’m directing, I’m solving problems, which are in everything we do: every show, scene, every shot. Richard Dreyfuss remarked once, that even much of acting is problem-solving.

DW: You poll wisdom from a broad range of sources in your book, from directors to actors to other roles on a film set. Do you have to balance outside ideas with your vision?

JB: I want ideas. I think anybody who doesn’t want ideas is ignoring the wealth of talent around them. Good ideas come from everywhere: camera people, actors, prop people, makeup, etc. There often is a germ of a good idea in one that may sound silly on the surface.

DW: Does that include the writer's vision when working on a series?

JB: You better be paying attention to the writer’s vision. It’s their script and their hard work that got us to this point. When I go in as a director, I do my best to understand what the writer has in mind. If I don’t understand that, I’ll make a mess of their script. If I have any suggestions for changes, I’ll go right to them and we work it out.

Remember, the writers are almost always the producers. Many shows have fourteen producers; twelve of them are writers, on staff all the time. If you’re the director, you’re there for six to eight weeks, and then you’re gone. Who’s going to win in this environment?

DW: And this seems to be the case from Mr. Mercedes with AT&T and The Audience Network to The Outsider at HBO—you see the same names in the credits. We noted that your films mix genres. As streaming is still surging alongside theaters, do you see shows and series as mixing genres?

JB: There are so many different kinds of genres. There are some sci-fi shows that are also comedies. I’ve directed the sci-fi Siren, which is set in a realistic New England village, and it has mermaids that transform into creatures that walk on two legs. Mermaids are often treated as comedic, certainly fanciful. But Siren is filmed in a very documentary style. The great show The Office is a comedy faux documentary. Anything is possible if it’s a good story.

DW: Your films also celebrated everyday people, thinking of Richard Dreyfuss, Roy Scheider, Ally Sheedy, and Matthew Broderick. Though superheroes appear to dominate the market for some people, do you think there's still appeal for that type of hero?

JB: People like to relate to characters in stories; it’s fun! Now, younger audiences may tune in to superheroes, but there’s always an audience saying, “This is us” when they see real people. If they can relate to a character, they may not be a hero, but they’re fallible. I was watching Homeland, and Claire Danes, who’s wonderful in it, but her character is so terribly fallible. When she beds the villain, we say, “No, don’t do that!” We like characters often because of their fallibility. With the show Succession, there’s hardly a likable character; everyone’s a mess. And we love it.

DW: Your career has spanned five decades as of next year. What are some of the biggest industry changes you've noticed? I realize this is a loaded question, and we talked about this a little.

JB: A big change over the last seven years is the explosion of streaming outlets. It’s not just the same old four networks that depend on advertisers for their revenues.

Two, we’ve gone from film to digital media. Three, Big studios are now run as a gig economy instead of long-term contracts. When I started in the mailroom at Universal, everyone, even me, was on contract. Now, employment deals are one job at a time.

DW: It sounds shaky though, and if it feels different, that ties back to why we go to the movies.

JB: Sometimes I’ll flashback to when directors like King Vidor or Billy Wilder or John Ford were in their heyday. Everyone was under contract, and you stayed at a studio for years. Now, you wonder if you go out to lunch, will they need you in the afternoon?

Another big change with series nowadays is that there’s a new job: producer-director. They are an experienced director who is there every day, working with this week’s director to supervise them and teach them all the dos and don’ts of that particular show. That producer/director is there to protect the ‘brand’ that is their show.

You often hear producers say is, “We don’t like surprises.” They’re protecting the brand that is their show. It reminds me of the time I was shooting in a McDonald’s in their kitchen, lining up a shot. On the wall was a blow-up of a Big Mac. It was up there so that anyone, even a brand-new employee, could assemble a perfect Big Mac. TV shows are kind of like that, the same every time. With a Big Mac, you can’t move the pickles to a different spot, put the cheese under the burger or leave the lettuce out. It’s the ‘pickle rule’ in directing. Don’t mess with the brand.

DW: As it is a brand, you know what you’re getting.

JB: Whether you’re in Tokyo or in California.

DW: I was in Tokyo as a kid, and I went to a McDonalds.

JB: Of course you did!

DW: I knew what I was getting. Finally, do you have a favorite cinematic moment? A shot, a scene—one you saw growing up or recently—that stands out?

JB: Oh, I’d have to say Once Upon a Time in the West, the opening ten minutes. I still watch it to this day. It’s a mystery where we have to puzzle out this wonderfully weird story unfolding before us. What’s going on we ask. We meet some of the baddest guys who were ever in Westerns. Charles Bronson, Jack Elam, Woody Strode waiting, waiting, waiting at a god forsaken train station out in the desert ? Why are these guys here? What do they want?

What happens is pure cinema. Me trying to explain it is like trying to explain Beethoven’s Fifth. You just have to hear it, or in this case, to see it. The ending of the sequence is a mind blower and one of the best openings to a movie ever!

Clip: Once Upon a Time in the West