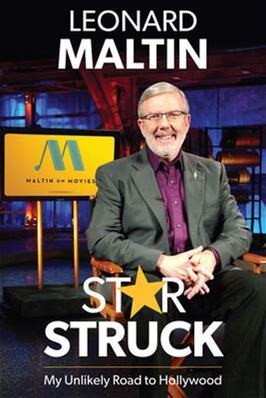

Film critic and Hollywood historian Leonard Maltin enjoyed thirty years on the hit television show Entertainment Tonight and continues to appear on Turner Classic Movies. He is best known for the perennial bestseller Leonard Maltin's Movie Guide and teaches the most popular class at the USC School of Cinematic Arts. He hosts the popular website leonardmaltin.com along with a weekly podcast, Maltin on Movies, with his daughter Jessie. We spoke about his new memoir, Star Struck, his most memorable interview over the decades, and his collage of favorite cinematic moments.

Order Leonard's book from GoodKnight Books here. Visit his website and listen to his podcast here.

Dave Watson: Congratulations on a great, memorable book. Was it hard to look back on your childhood? You seem to recall it vividly.

Leonard Maltin: No, it wasn't, I am not as in touch with my inner child as much as some people I know, who have the immediacy that they can conjure up is something I cannot do. But I remember the things that count, the things that matter to my way of thinking.

DW: Relationships seem long-lasting. You still have childhood friends and friends from your twenties and thirties. Would you say that's a key to your success?

LM: It's one of them, for sure. Having friendships that last is very enriching ... nourishing, I would say. There's a closeness, there's a shorthand in the way we deal with each other, we can press each other's buttons for instant nostalgia or recollection. I saw a sampler in a catalogue last year that said, "Old friends are the best friends." I subscribe to that.

DW: You enjoyed thirty years on Entertainment Tonight, and you are also a film historian and you host Turner Classic Movies. Would you say there are some films, some gems before we were born, that have stood up to the test of time?

LM: Oh absolutely, and I'm not alone in that belief or there wouldn't be a Turner Classic Movies on the air, and contrary to what I've heard and read, it's not just with people with grey and blue hair. I can vouch for that because every year here in Hollywood they have a classic film festival where people fly in from all fifty states and beyond, and it's a varied demographic. There are college students, there are people like me who get hooked in adolescence and never lose that love and devotion to classic cinema.

DW: You're also best known for the perennial best seller Leonard Maltin's Movie Guide, and teach the most popular class at the USC School of Cinematic Arts. What is that class?

LM: It's a class that I inherited, not one I created, but I'm in my twenty-third year of doing it. In the early '60s a very prominent film critic named Arthur Knight talked to the department and said, "We're in the backyard of Hollywood and you should have these people come and talk to you," and they agreed. Alfred Hitchcock came, and John Cassavetes came, the old guard and the new guard, and so Arthur taught that for many years, then passed the baton after he retired to Charles Champlin who was the senior film critic for The Los Angeles Times, and I'm just the latest one to take hold of this course. George Lucas took this class. Ron Howard took this class, so it has a really interesting history, and all it consists of, well, we talk first.

One of the first things we do is talk about last week's film. I want to get students to do is articulate their feelings. Just because you loved it doesn't mean the guy or girl next to you loved it, maybe they hated it, and opinions are valid. No one is right or wrong. I'm never bored because I meet interesting people every week. We had the latest James Bond last week the night before it opened and we had the two film editors. It was a very long movie and a lot of footage to sift through to get those actions moving crisply. Editing is kind of the invisible art, you don't notice it unless they've done a bad job, and yet part of what makes the job interesting, what makes my job as the moderator, is the human factor: you're not just hiring a mechanic, you're hiring a partner for many months, so if you don't get along, some basic eh...human level, if you don't get along, you're not going to do good work and you're not going to have a good time.

DW: It's intimacy as well.

LM: Intimacy and also diplomacy. You're not the only two people in that room. Producers, spouses of producers will march through that room, and sometimes there are situations where you're put in the middle of a decision, the producer feels one way and the director feels another and you're forced to take sides. How do you play that as an editor? Those things are valuable in any job. They call them people skills now.

DW: Social skills at some point. You've met people behind and in front of the camera. Would you call your position unique?

LM: Oh no, there are so many people writing about film now online. You couldn't count the number of blogs and websites now, many with many contributors.

DW: You said you get students to talk about their feelings, and that's one of the things about the medium is film sticks with you for days, often much longer.

LM: If it's good, or awful! (laughs)

DW: Or we can forget about it a month later, we forgot we've seen that movie. Of all your interviews, is there one that sticks out, one that's particularly memorable, or surprising over the decades?

LM: Well my favorite interview was Katherine Hepburn, and I got to interview her four times. I first interviewed her in the late 1980s, and she wasn't a recluse, but she wasn't terribly willing to make herself available for interviews. She had just made an NBC made-for-TV movie and agreed to do two interviews, The Today Show, and Entertainment Tonight, and E.T., to my surprise, chose me, flew me to New York, and I interviewed her in her townhouse on East 49th Street, her home. It was just a glorious, glorious day. There are some amusing sidelights to that journey that I tell in the book.

DW: Yes.

LM: And I wouldn't be able to tell them if I hadn't made a journal entry. I'm not someone who keeps a journal, I wish I were, but on days that I know are special, I've taken the time and written them down and been able to call on those in writing Star Struck, but it was just wonderful. She was my favorite interview because she is who she is but she's also blunt, colorful, opinionated, not a dull bone in her body.

DW: Yet you're in the presence of grandeur, of legend.

LM: And she didn't carry herself that way. She told stories on herself, when she first went to Hollywood and admits to being haughty, and in some cases overly stubborn, even anti-social. You know she won four Academy Awards, was nominated for many more, and she never went, never showed up, and I asked her about that. She said, "Oh, that was just me being my arrogant self," or something like that.

DW: So being dismissive, was she hinting that you don't want to ask any more about that?

LM: No, I don't think that was it, I think she was wearing her eccentricities as a badge of honor.

DW: Would you say that's non-Hollywood in a way?

LM: It just labels her an iconoclast.

DW: I believe her last Academy Award was for On Golden Pond in 1981, and many people forget what a vibrant young actress she was. The Philadelphia Story comes to mind.

LM: Hard to beat that one.

DW: She was such a presence on the screen, portraying many strong women.

LM: She didn't look like anybody else, she didn't sound like anybody else, it was sort of a shock for... it took people time to get used to who she was.

DW: On and off screen?

LM: I can't vouch for her offscreen, but onscreen yes. Howard Hughes liked her! You mention The Philadelphia Story. It was written for her by the playwright Philip Barry, who wrote Holiday for her, but in the late 1930s she was labeled box office poison because she'd had some failures, and it was not only a slap in the face ego-wise, but it was bad for business, so Philip Barry wrote this play with her in mind, Howard Hughes fronted the money for her to buy the screen rights, so when the studios came calling, she herself negotiated Louis B. Mayer herself, and it's no accident that Cary Grant and Jimmy Steward were her leading men.

DW: She herself? No agent or attorney present?

LM: Well (laughs) she and Louis had the same lawyer and she said to this famous, imperial mogul, "You wouldn't cheat me, would you Louie?"

DW: Putting him on the spot, and taking the moral high ground. Are there any movies from that era, say, the 1940s, that you re-watch today?

LM: Oh sure, sure. My very favorite movie is Casablanca. I try not to re-watch it too often so that I have fresh eyes and ears when I come back to it. And then The Maltese Falcon, the inevitable Citizen Kane, where I notice new things each time I watch it, the mark of a great movie, I think. You know, if you ask for a top five, under duress, I'll give you a top five, but it quickly grows to five hundred. They're all related. I like the era, the story and the stars, but, eh, my wife and I were watching one the other night and we said, "Oh, look at that car!" It was from the fifties. the other night we saw Mystery of Edwin Drood with Claude Rains, and the Art Direction was meticulous. Alison and I noticed the fire screens from that era. Do you know those?

DW: I confess I don't.

LM: Well now you're forcing me to define it and it won't be easy. It's usually a square or rectangular piece of embroidery, usually, on an easel, and if you're sitting by the fire and didn't want to feel the full intensity of that fire, you used a fire screen, which was attractive enough for you to place in your living room or wherever, and it prevented you from getting heat stroke.

DW: Because that was an actual condition back then.

LM: I don't know but we'll go with it.

DW: But you notice in a film from 1935, now eighty-six years ago. Martin Scorsese talks about that, that film can transport you back in time, to another time and place instantly.

LM: And I tell my students that every film is a product of its time, a mirror of its time, whether it intends to be or not, because inevitably the style of clothing, the style of language, slang, gives you clues to when it was made.

DW: And yet Once Upon a time ... in Hollywood, which came about just over two years ago, evokes 1969, but I felt like it was relevant to today, and sometimes it's hard to put your finger on why.

LM: Yes.

DW: And there are reasons why it reaches such a wide audience.

LM: And I'm sure it opened a window on a period that a lot of younger viewers today didn't know about.

DW: Like JFK in 1991 did. Has another film done that for you, inspired you to get to know another era?

LM: Cumulatively, that's why I immerse myself in the movies of the '30s and '40s.

DW: What would you say have been the biggest changes or single biggest change since you started watching movies?

LM: Censorship was still a factor in moviemaking in Hollywood, so the late 1960s. I was born in 1950, so when I started going to the movies, by myself or with friends, my parents had nothing to fear. I was never going to hear a swear word, or see a sexual encounter, I was never going to be exposed to graphic violence, those things were just verboten.

DW: By the studio system? Who?

LM: By the Motion Picture Association, which is essentially a trade organization, to which the studios belonged, it was a voluntary thing. It was internecine warfare at times, but they agreed to abide by a code, a certain code. You know, in 1939 when Clark Gable says, "Frankly, my dear, I don't give a damn," David O. Selznick had to go and argue that case in front of the Motion Picture Association, because you just didn't say "Damn" in a Hollywood movie. Now that code was revised in 1934, so films of the early '30s are called pre-code films. That's when you see Tarzan and Jane and Jane is in a skimpy outfit, and by the time the sequel came out, they had to put her in a Mother Hubbard or equivalent. Betty Boop, an iconic cartoon character, is always pictured in a skirt and garter; they had to lengthen that skirt and take out the sexual innuendoes that make up parts of that cartoon, so "Damn" would be perfectly piece of dialogue then, "Hell" and "Damn."

DW: Sometimes violating that code is the point of some comedies.

LM: Yes, yes, and the cleverer writers and directors, mostly writers, had to find a way to subvert the code and pull the wool over the eyes of the sensors, so that's a big, big change. It was paralleling the social revolution of the 1960s. That's when you saw The Graduate, Who's Afraid of Virginia Wolf?, Bonnie and Clyde, these real game-changer films, American films.

DW: And very high profile, very mainstream. Glenn Frankel just wrote a book on Midnight Cowboy.

LM: Oh yes, I like Glenn and I like his work.

DW: Yes, and Midnight Cowboy, the first rated-X movie to win Best Picture, is just as affecting today, and yet very course for its time. You also see that in the Best Picture winners from the early '60s: West Side Story, Lawrence of Arabia, to The Sound of Music in 1965, then Who's Afraid of Virginia Wolf? in 1966, The Graduate and Bonnie in Clyde in '67 and Midnight Cowboy in '69. You see the big shift.

LM: Yes, a major shift.

DW: Do you have a favorite cinematic moment? One that inspired you growing up or recent?

LM: Oh I have more than one. You're putting me on the spot again! In my mind right this minute I'm seeing a collage.

DW: And in the middle of that collage would be...

LM: Charlie Chaplin, Laurel & Hardy, and Midnight Cowboy...

DW: To juxtapose....

LM: And Lawrence of Arabia, and so many, many other films. I admit I'm not a fan of remakes, but I am curious to see what Steven Spielberg has done with West Side Story, with the screenplay by Tony Kushner, that's one I want to remain open-minded about.

DW: I am waiting with great curiosity as well. The 1961 version is vivid to many as well.

Clip: West Side Story

Founder and editor of Movies Matter, Dave Watson is a writer and educator in Madison, WI.