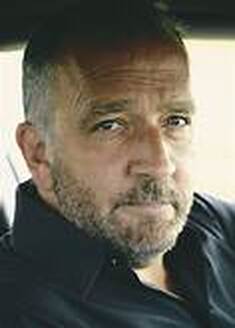

Born and raised in Washington, DC, GEORGE PELECANOS is the bestselling author of twenty-one books, among which he is the recipient of the Los Angeles Time Book Prize twice, the Raymond Chandler award in Italy, the Falcon award in Japan, and the Grand Prix Du Roman in France. He has served as producer on feature films and as producer, writer, and story editor on the acclaimed HBO series, The Wire, for which he was nominated for an Emmy. Most recently he served as Executive Producer and Showrunner for WE OWN THIS CITY, chronicling the rise and fall of the Baltimore Police Department's Gun Trace Task Force. We spoke recently about his sustained writing career of over thirty years, the films that inspired him growing up, and what's next for the prolific author.

Visit George Pelecanos's website here.

Dave Watson: I racked my brain for the first question. You just finished Executive producing, writing and developing We Own This City, and seem like a novelist first and foremost. Where are you now?

George Pelecanos: I just finished doing the publicity for We Own This City which premiered last Monday night, so I’m done with that. I’m writing something for HBO, started writing this week. I’m doing an adaptation of a John D. MacDonald novel called The Last One Left. I’m doing it with Megan Abbott, a novelist, screenwriter, and friend, so we’re partnering up on that.

DW: I’m hearing a trace of Derek Strange here where he sits down and gets right to work, in a cafe or sitting in his car. Do you see part of yourself in him?

GP: I don’t know what else to do. I don’t have a lot of hobbies, I don’t play golf. I do some physical stuff, I kayak, I ride my bike, but that’s just something to clear my head so I can get back to work and keep writing, and I have no plans for retirement. The plan is for me to, you know I’ll eventually age out of the television and movie business and then I’ll write books until my death.

DW: And you plan to stick to it. When did you discover you were a writer? Was it something you chose, or something that came over you? Some people feel like they are chosen to do something. When did you have this realization?

GP: I was a movie freak before anything. I wasn’t much of a reader when I was a kid. I was fortunate to be a teenager in the ‘70s, the golden age of film. Even before that as a boy in the ‘60s I’d go to movies, go to movies with my dad and I started working for my dad when I was eleven. He had a diner downtown and I would deliver food for him on foot. When I was out there, just to alleviate the boredom of walking around the city with bags of food in my hand, I’d make up stories that would last a whole week. I would serialize them, and felt like I was making movies in my head, but what I was really doing was writing books, like chapters progressing in my head. So my ambition as a kid was to make movies eventually.

What happened was I got waylaid in college. I went to the University of Maryland and took an elective class in crime fiction; a teacher there named Charles Mish turned me on to books. What turned me on about crime fiction was it was the first kind of writing that I’d read that spoke to my world, the blue collar world, parts of the city I knew. A lot of these American novels are about people who succeed. In these crime novels people don’t often succeed as they often don’t in life, but they do have small victories. That was really attractive to me. So I decided then that I’m going to be a novelist. For the next ten years I read a ton of books while living a full life. I was a bartender, a womens’ shoe salesman, worked a lot of retail, in kitchens and at the time I didn’t think I was getting material, I was just trying to make a living and I’ve used all that in my books. I’ve lived a full life.

DW: Family is a theme in your books. It’s something your characters go into, but also take them out into the streets of DC.

GP: It’s not just the nuclear family, it’s finding a family at work. I was fortunate to come from a very loving home which is important in my development. But I couldn’t wait to go to work, to go into the sales floor or kitchen because that was my family too. There were a lot of oddballs and freaks, outsiders who really find a home in the workplace, which is what I was.

DW: You follow characters and they behave a little differently at home and at work. How do you achieve that? Do you imagine the characters first or do you write and they come out?

GP: I don’t outline. To this day I’ll think of a situation to get me in the narrative. Not to sound too mystical but after a while the characters write themselves. They start to do things based on how you’ve created them that drive the plot forward. Even if I’m screenwriting, I’ll get beat sheets but I don’t often follow them.

DW: I think it was Robert Frost who said, “Writing is live driving through the night. You can see just ahead of you, but if you drive all night, you’ll get there.” Do you agree with that?

GP: Yeah. I don’t get scared anymore, because after twenty-one novels now, after that many books, you sort of know it’s going to be alright. I just have to do the work. I have to sit down and work every day. If I’m writing a novel, I write seven days a week in a very rigid schedule, and write in two shifts. The first shift is writing and the next shift is rewriting. I know it’s going to be alright because it’s historically been alright.

DW: How do you keep from not getting shook up, or how did you keep from getting shaken up in the early stages?

GP: You know what, it didn’t really matter because first of all when I wrote my first book I didn’t know if anyone was ever going to read it. For my first five novels the advances were so low that it also didn’t matter. I wasn’t writing for the publisher and it gave me a lot of freedom because no one was micromanaging me. I was learning how to write as I went along, and I didn’t worry about it. I didn’t stress over it.

That’s probably why the early books are so raw and different than anything else that was being written at the time. They were punk rock novels. We had a real big punk rock movement here in DC that I was a fan of, I’d go to shows, and figured out a lot of these people in these bands had no real musical training. But they were artists.

So for someone to say, “You have to go to the Iowa Writers’ program, you have to go to grad school and all that,” I’m like, “No, I’m akin to a punk rock musician. I’m just going to pick up pick up my pen and play.” I mean, why not me?

DW: Going to back to film and the golden era of the ‘70s, there were some good crime novel adaptations in the ‘60s and ‘70s.

GP: I think the New York crime films that were a time capsule of New York. I also saw the exploitation, the blacksploitation movies, kung fu. I loved movies, I’d haunt the theaters, whatever was playing I’d go see it. I loved movies like Rolling Thunder, Walking Tall, the original, and the blacksploitation films like The Mack, Superfly. Curtis Mayfield is probably my artistic hero. That was sort of a bible movie for me. When the kung fu movies came out I was right there.

You know, that was my film education. We had repertory theaters here in DC like the Circle theater and the Biograph. They changed movies every two days.

DW: Unheard of these days.

GP: I’m going to jump around here: the two guys who owned the Circle theater were these two Greek American guys named Jim and Ted Pedas. They ended up owning about eighty theaters in DC area, and then they got into film distribution. They had a relationship with the Coen brothers and produced three of their early films: Miller’s Crossing, Barton Fink, and Raising Arizona out of a little office here in DC., and they distributed Blood Simple. I’d read in the trades that they’d picked up John Woo’s The Killer. I’d seen it at film festivals, and I wrote them a letter and I said I want to come work for you guys and help you distribute this film, and they let me in. I worked for them for nine years while I wrote novels and we put out The Killer and we broke John Woo in the States.

Anyway, that was that, my relation to theaters in Washington, but I have to go back to the movies of the ‘60s. They were kind of big balls-action films: Magnificent Seven, The Great Escape, The Dirty Dozen, Robert Aldrich, the Leone films I saw in the late ‘60s as a kid, and most significantly, The Wild Bunch. It changed my life.

DW: Good for you for mentioning that.

GP: I went with my dad to the Allen Theater. I was eleven years old. It was R-rated. I remember the woman at the window said to my dad, “Are you sure you want your son to see this?” You know, back when people gave a shit. When we walked out I said to my dad, “I want to do that.”

I always waited to see the credits and I saw it was written by a guy named Walon Green. That particular movie changed my life.

DW: It’s also an anti-hero western tied to big ideas. I still remember to this day the opening shots and scenes of that movie, and it was my introduction to Hollywood’s golden boy William Holden. You saw Hollywood heavies, and it became about old men in changing times. Your books tie to bigger ideas as well, at different points, sometimes toward the end. Do you start with the ideas or do they, say, jump out at you when you’re writing and progress through a story?

GP: If you look at my books, there’s a sort of progression. Something happened to me. The first five are straight up crime novels. Around that time, all my kids are adopted, my wife and I went to Brazil to get our second son. We got stuck down there, and we had to figure out who to pay off so that we could come home. I eventually figured it out but we were down there for three months. Brazil doesn’t have the social safety net that we do in this country, and the poverty is right there in your face, and the violence, there are cities where you can’t walk around at night, and there are people with armed guards living behind walls. And when someone is that hungry, they’ll murder you. I came home a little bit radicalized. We have the same divisions in our country between the haves and have nots, but we mask it well with things like food programs and welfare and so on, but the injustice is still here. You can see a change in my books about that time where I started to tackle social issues more.

Specifically in my city of Washington, DC the divide is right in your face. You go down to North Capitol Street which is the street that runs right into the Capitol building, the dome. You can stand on Florida Avenue and see drug addiction, the poverty, the violence, you see all these things right in the shadow of the Capitol dome, and I’ve been writing about it ever since. It’s what drove me to write about that in television versus escapist television. It’s a medium where I can reach more people than I do in my books, and I can talk about these issues I want to discuss.

DW: I lived on D Street right behind the Madison Building and we’d see $1,000-plate dinners up the street and just a few blocks away we’d see addled people we presumed were drug addicts. Is that contrast still that close together to this day? I’ve also heard it’s more gentrified now versus back then.

GP: When I was growing up DC was seventy to eighty percent black. In the song Chocolate City, they say, “Blood to blood, players to ladies, the last percentage count was eighty. You don’t need the bullets if you got the ballots, CC.” Now it’s less than fifty percent black. So the illusion is that things like poverty have gone away but they’ve just been pushed to different places.

DW: Author Lee Child said that as a side note in one of his books, that all it does is get moved around. That’s a steep drop though. Where did they go? Outlying suburbs or different states?

GP: Prince George’s county, Maryland was white-blue collar when I was growing up and it’s now over ninety percent black.

DW: Where is it exactly?

GP: Right on the southeast border. You know there are eight wards in DC, they call Prince George’s county Ward Nine, which people in PG county hate.

DW: Maybe they’ll get used to it. You show a different side to DC in your books, and we’ve seen traces of it in series such as House of Cards. You name specific streets and places in DC and though it’s unfamiliar, I find it never gets in the way of the story.

GP: I hope so. I’m leaving a record of the city behind, that’s what I’m trying to do. I’m writing it for Washingtonians. When I was on The Wire and We Own This City, we made those for Baltimorians. The Deuce was for New Yorkers. That’s what we really care about, the people we’re writing about. It’s important to me.

If I remember a white house with blue shutters on the corner of Fifth and D, I’m going to go down and make sure that house has blue shutters. Some people won’t care about that, but I care, because it’s leaving a record.

DW: Right, and it’s a historical record. Music also plays a role in your stories. Has music always been a big part of your life?

GP: Yes, there’s a room in my house with my stereo and that’s what I do every night is play music and read.

DW: Same thing with cars in your stories. You seem to go into characters’ homes and note what their couches look like. Do you imagine that or do you do research?

GP: In terms of the homes, when I figure out who the character is, I’m going to know what their house is like. I’m very sensitive to detail, and I am a car freak. I just sold my Bullit Mustang to my nephew so I don’t have that anymore. But I do have an Impala SS in my garage.

If you look at my scripts they’re like my novels. Most Hollywood scripts have a lot of white space, and mine will have dense, descriptive paragraphs. I’m going to control the finished product the way I do a novel. I don’t leave anything to chance. I art direct. The cars are specifically named, and what people are wearing is named, and I work with all these talented people who head these departments. On one hand someone could say I’m micromanaging but I think people appreciate it because they know I care.

DW: That’s an important part of leadership. I want to go back to one movie you name in a book, The Outfit with Robert Duvall, a little seen film, and what are some of the writers that inspired you growing up or read in college that you said, “Wow, that’s a writer.”

GP: You know, somebody who’s a popular writer who’s not popular with academics is John Steinbeck. Academics always put him down because the symbolism is obvious, but that doesn’t mean it’s not smart or worthy. Of Mice and Men is a wonderful book–just because it’s universally understood doesn’t mean it’s inferior in any way. The Red Pony is mind-blowing, it’s about life.

During the pandemic I read a lot, more than I normally do even, I got into the books of Joyce Carole Oates. I think she’s fantastic, specifically Because It Is Bitter, And Because It Is My Heart blew my mind.

Of the crime writers, David Goodis of the noir writers is a favorite of mine. And there were always books, they were crime novels, but they were just good books that influenced me: True Confessions by John Gregory Dunn, Cutter and Bone by Newton Thornburg, Tapping the Source by Kem Nunn. You can call them crime novels but they’re just good books.

DW: Charles Ardai of Hard Case Crime talked about how some of the greatest books of all time, at the center, have a crime.

GP: I just read this book they put out that won the Edgar award.

DW: Kestrel’s book, Five Decembers.

GP: It’s excellent. I collect those Hard Case Crime books. To me they’re like the old Black Lizards. Anything with that imprint on it is going to have worth. You mention The Outfit, that’s Richard Stark, those books are great.

DW: So you read quite a wide swath of books. Do you have a favorite cinematic moment?

GP: There’s a moment in The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly, where Clint Eastwood goes into a blown-out church, there’s nothing left really, there’s a dying soldier there. He’s smoking a cherub, and he gives a guy…there’s no dialogue in the scene, and Ennio Morricone’s score comes up, I think the music cue is called Mort de soldat, or Death of a Soldier.

Can I give you a few?

DW: Of course you can!

GP: Clint Eastwood again in The Outlaw Josey Wales. When he has the final confrontation with John Vernon, they’re talkin’, he says, “I think I’m gonna ride south.” John says, “What are you gonna do?” Clint says, “I reckon I’ll find him and tell him the war is over. We all died a little in that damn war.” That’s a wonderful scene. It’s Jerry Fielding who does the score there. He incorporates a little bit of “Rose of Alabama” in there, which was used earlier in the film.

DW: Why does that scene resonate with you?

GP: It’s a brilliant marriage of image, writing, acting, and score. They’re talking around each other, and the writing is just outstanding. He’s saying, are you going to continue to seek vengeance, because they’ve been after each other the entire movie, and he’s letting that guy off the hook. He’s saying, I’m done.

Going way back, Angels with Dirty Faces. It’s an old movie with Jimmy Cagney and Pat O’Brien and the dead-end kids. In the beginning they’re kids running from the police, Jimmy gets snagged trying to climb the fence, and Pat O’Brien goes over the fence. Jimmy gets put in the system which leads to a life of crime, while Pat O’Brien becomes a priest. You go fast forward now and Cagney has befriended these kids, the dead-end kids, and they look up to him as a hero. Jimmy Cagney gets convicted of a murder and he’s going to be put to death and is going to jail.

Pat visits him in jail and says, “These kids look up to you. I know you’re going to go to your death as a tough guy. Do one good thing in your life and don’t go out like that.”

Jimmy Cagney says, “Get the hell out of my cell.”

The kids are outside listening. As he’s walking to his death in the electric chair, very proudly and Cagney-esque, he suddenly breaks down in tears and starts begging for his life. So the kids listen to him being a coward at the end.

In the last scene Pat O’Brien is with the kids and says, “Let’s say a prayer for a kid who couldn’t run as fast as me.”

DW: A lot of yours have to do with humanity and humility, especially the last with forgiveness and caring, almost when we least expect it.

GP: It goes with, speaks to my idea that there really are no villains. This show we just did, these cops that got caught and sent up to prison, I don’t look at them as villains, I look at them as victims also in the system. Nobody comes out of the police academy saying, “I’m going to rob people, re-sell drugs on the street, or bully people.” But the system turns them into that, it’s flawed, the mission is flawed and they’re victims too. When you tell police officers to lock people up en masse, just arrest everybody, you start to get cynical about everything. Not all cops, but these cops did, they became that. They weren’t villains, they were victims also.

DW: That reared its head in your book Hard Revolution. That sounds like quite a pivotal time in your history.

GP: The ‘68 riots were the pivotal moment in our modern history, it changed everything in this town. It also, and this is a controversial view of mine in a way, to me it accelerated the civil rights movement by ten years in one weekend. Up to that it had been peaceful demonstrations. When white America saw what is possible when you don’t do anything, or you move too slow. They took notice, and things change.

Clips:

The Good, the Bad, and The Ugly

The Outlaw Josey Wales

Angels Have Dirty Faces

Founder and Editor of Movies Matter, Dave Watson is a writer and educator in Madison, WI.