Dave Watson: You worked as a studio liaison for Sony Pictures.

Ken Miyamoto: Yes. I initially started at Sony in the lower end of the totem pole as a security guard. My wife and I had moved, by chance, to a new apartment right across the street from the Sony studio lot back in 2002. I used to jog around the lot, which was about a mile around. I did it for the workout, but primarily enjoyed peeking into each and every gate as I passed. I saw the sound stages. Movies being made just beyond those walls. And I saw the endless stream of Sony employees and crew coming in and out of the lot with their Sony ID badges. I wanted in. So one day I walked up to a security guard and asked, “How do I get a job here?” Two weeks later, I was a Sony security guard. I finagled my way into a coveted post at the North Thalberg lot, known as the prime VIP lot for visiting actors, producers, directors, and executives. I was on a first name basis with Sony execs like Amy Pascal and others. We’d also see A-List talent coming through. I’d get perks and Christmas presents. But at the end of the day, it was a security guard job. That wasn’t what I wanted to be. This was just my way in. My way onto the lot. I had that coveted Sony ID badge and could finally come and go as I pleased. I worked my way into an office job thankfully and soon became a studio liaison for incoming television and feature productions, as well as for incoming executives and production companies. I’d handle their parking and studio access needs, their drive on passes, their Sony IDs, etc.

It was a great position to be in to network. I worked with some big productions from Sony and other studios. I constantly worked with top talent. I was fortunate enough to work a lot with the likes of Adam Sandler and his Happy Madison crew. Sandler and I played basketball together now and then. We had discussions about Madison, where the late Chris Farley was from. And Sandler was even the one responsible for my ACL tear as we went one on one during a basketball game. It’s not too often when you have a $20 million per picture movie star carrying you off of the court and fetching you water. He’s a great guy. It was moments like these with him and many other Hollywood players that made the job so much fun. And I had free reign on the lot with a golf cart, which I sorely miss.

DW: You were also a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures. Does a script reader do just that?

KM: Through my studio liaison job, I met a development executive working under the late John Calley, a former studio head and producer. A Hollywood legend. I had always wanted to get into development. I had interned for director Randal Kleiser (He directed “Grease”) with whom I had done script coverage for. I took a chance with this development executive and told him that if he ever needed a script reader, I’m game. By chance, he did need a reader. I sent him some coverage samples and within a week or so, I was now a Sony script reader. My dream job at the time.

A script reader does just that… read scripts, as well as novels for possible adaptations. The studio has incoming screenplays from novice and even established screenwriters. Literally hundreds upon hundreds of scripts each month. So many that there has to be some filtering mechanism within the development system. That’s what a script reader does. They read through those scripts and write studio coverage on them, grading the script’s different elements, matching the wants and needs of the studio as far as what type of projects they are looking for, and basically weeding out the bad scripts from the good. 95% of the scripts that come in are horrible. Just outright bad or not ready. 4% are average or slightly above average. Less than 1% are great and then a tiny percentage within that top 1% are worthy of packaging, acquiring, developing, and producing.

It is a powerful position to be in. It is also the best education a screenwriter will ever receive as far as what to do and what not to do. And lastly, it is a really difficult job. It’s not just about reading scripts and tossing them aside to move onto the next. Writing studio coverage takes time. With each script, you have to write notes and you have to write a detailed synopsis because that is what producers and executives rely on. Anything that gets a PASS grading overall, which is 95% of them, generally never get read by the powers that be. The 4% that get a CONSIDER grading overall might be read. The 1% that get a RECOMMEND grading overall will be read.

So yes, the script reader has a lot of power. But it is tough, especially considering that you still have to write notes and a synopsis for the 95% that are horrible scripts. But again, it’s the best education a screenwriter will receive. Better than any guru book or film school class.

DW: And a story analyst? Many people I meet appear already at least amateur story analysts.

KM: Anyone can analyze a story, but they are mostly doing so through their own subjective viewpoints. A studio story analyst/script reader is there to look at the script through the film industry eye. What demographics does X script appeal to? How are the concept, story, and characters different or similar to successful films that have been released? Is the script very castable? Will it attract talent? Is it more concept driven or is it story or character driven? What are the strengths and weaknesses of the concept, story, and characters? What needs work? What doesn’t? Why? Etc.

That’s what a story analyst/script reader does. It’s not easy. It’s not just about whether or not the script reader likes X script either. If I’m a studio reader and I recommend a script that appeals to me personally, but doesn’t fall under the umbrella of want or need that the studio has, I’m fired. This is the position where you can and will learn the most. You’ll truly learn if you have what it takes to be able to work in this environment. Because it’s not show art, it’s show business. You have to be able to become a hybrid of the artistic storytelling side of it AND the business side. And in turn, that’s exactly what you need to become in order to be a successful working screenwriter. The moment you can be objective about your own concepts and scripts is the moment where you’ve taken a huge leap ahead in the game.

DW: Who were you working with? Directors? Executives?

KM: As a studio liaison, I was working with everyone above and below the line. From crew to talent, directors, producers, executives, etc. As a script reader/story analyst, I was working primarily with development executives and producers.

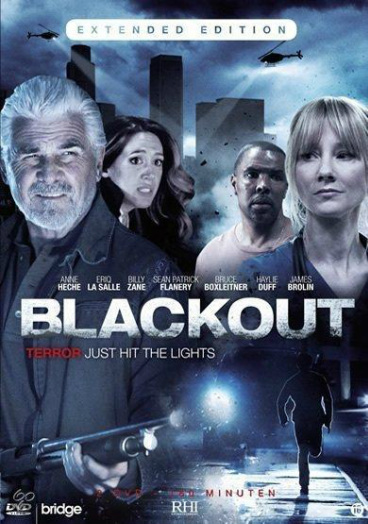

DW: You are a represented and produced screenwriter, congratulations! You wrote Blackout, a miniseries, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, and James Brolin. What was this series about and how did the idea come about?

KM: Blackout was an assignment. I had met an Executive Producer and development executive who happened to be from my home state of Wisconsin. This was after I moved back to Wisconsin to raise our children close to family.

Ken Miyamoto: Yes. I initially started at Sony in the lower end of the totem pole as a security guard. My wife and I had moved, by chance, to a new apartment right across the street from the Sony studio lot back in 2002. I used to jog around the lot, which was about a mile around. I did it for the workout, but primarily enjoyed peeking into each and every gate as I passed. I saw the sound stages. Movies being made just beyond those walls. And I saw the endless stream of Sony employees and crew coming in and out of the lot with their Sony ID badges. I wanted in. So one day I walked up to a security guard and asked, “How do I get a job here?” Two weeks later, I was a Sony security guard. I finagled my way into a coveted post at the North Thalberg lot, known as the prime VIP lot for visiting actors, producers, directors, and executives. I was on a first name basis with Sony execs like Amy Pascal and others. We’d also see A-List talent coming through. I’d get perks and Christmas presents. But at the end of the day, it was a security guard job. That wasn’t what I wanted to be. This was just my way in. My way onto the lot. I had that coveted Sony ID badge and could finally come and go as I pleased. I worked my way into an office job thankfully and soon became a studio liaison for incoming television and feature productions, as well as for incoming executives and production companies. I’d handle their parking and studio access needs, their drive on passes, their Sony IDs, etc.

It was a great position to be in to network. I worked with some big productions from Sony and other studios. I constantly worked with top talent. I was fortunate enough to work a lot with the likes of Adam Sandler and his Happy Madison crew. Sandler and I played basketball together now and then. We had discussions about Madison, where the late Chris Farley was from. And Sandler was even the one responsible for my ACL tear as we went one on one during a basketball game. It’s not too often when you have a $20 million per picture movie star carrying you off of the court and fetching you water. He’s a great guy. It was moments like these with him and many other Hollywood players that made the job so much fun. And I had free reign on the lot with a golf cart, which I sorely miss.

DW: You were also a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures. Does a script reader do just that?

KM: Through my studio liaison job, I met a development executive working under the late John Calley, a former studio head and producer. A Hollywood legend. I had always wanted to get into development. I had interned for director Randal Kleiser (He directed “Grease”) with whom I had done script coverage for. I took a chance with this development executive and told him that if he ever needed a script reader, I’m game. By chance, he did need a reader. I sent him some coverage samples and within a week or so, I was now a Sony script reader. My dream job at the time.

A script reader does just that… read scripts, as well as novels for possible adaptations. The studio has incoming screenplays from novice and even established screenwriters. Literally hundreds upon hundreds of scripts each month. So many that there has to be some filtering mechanism within the development system. That’s what a script reader does. They read through those scripts and write studio coverage on them, grading the script’s different elements, matching the wants and needs of the studio as far as what type of projects they are looking for, and basically weeding out the bad scripts from the good. 95% of the scripts that come in are horrible. Just outright bad or not ready. 4% are average or slightly above average. Less than 1% are great and then a tiny percentage within that top 1% are worthy of packaging, acquiring, developing, and producing.

It is a powerful position to be in. It is also the best education a screenwriter will ever receive as far as what to do and what not to do. And lastly, it is a really difficult job. It’s not just about reading scripts and tossing them aside to move onto the next. Writing studio coverage takes time. With each script, you have to write notes and you have to write a detailed synopsis because that is what producers and executives rely on. Anything that gets a PASS grading overall, which is 95% of them, generally never get read by the powers that be. The 4% that get a CONSIDER grading overall might be read. The 1% that get a RECOMMEND grading overall will be read.

So yes, the script reader has a lot of power. But it is tough, especially considering that you still have to write notes and a synopsis for the 95% that are horrible scripts. But again, it’s the best education a screenwriter will receive. Better than any guru book or film school class.

DW: And a story analyst? Many people I meet appear already at least amateur story analysts.

KM: Anyone can analyze a story, but they are mostly doing so through their own subjective viewpoints. A studio story analyst/script reader is there to look at the script through the film industry eye. What demographics does X script appeal to? How are the concept, story, and characters different or similar to successful films that have been released? Is the script very castable? Will it attract talent? Is it more concept driven or is it story or character driven? What are the strengths and weaknesses of the concept, story, and characters? What needs work? What doesn’t? Why? Etc.

That’s what a story analyst/script reader does. It’s not easy. It’s not just about whether or not the script reader likes X script either. If I’m a studio reader and I recommend a script that appeals to me personally, but doesn’t fall under the umbrella of want or need that the studio has, I’m fired. This is the position where you can and will learn the most. You’ll truly learn if you have what it takes to be able to work in this environment. Because it’s not show art, it’s show business. You have to be able to become a hybrid of the artistic storytelling side of it AND the business side. And in turn, that’s exactly what you need to become in order to be a successful working screenwriter. The moment you can be objective about your own concepts and scripts is the moment where you’ve taken a huge leap ahead in the game.

DW: Who were you working with? Directors? Executives?

KM: As a studio liaison, I was working with everyone above and below the line. From crew to talent, directors, producers, executives, etc. As a script reader/story analyst, I was working primarily with development executives and producers.

DW: You are a represented and produced screenwriter, congratulations! You wrote Blackout, a miniseries, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, and James Brolin. What was this series about and how did the idea come about?

KM: Blackout was an assignment. I had met an Executive Producer and development executive who happened to be from my home state of Wisconsin. This was after I moved back to Wisconsin to raise our children close to family.

|

I took a chance and pitched some of my spec scripts. He read them and was very impressed with the writing so he offered me a writing assignment, which wasn’t Blackout. The first assignment was a drama for a TV movie. It didn’t go to script, but I received a good payday for the development work. A couple months later, he came to me with Blackout.

It was set as an event miniseries and was pre-sold in foreign territories, meaning that they sold the concept for distribution and now had to develop the script and produce it. They did have an existing screenplay, but it wasn’t that great. He pitched me the concept of “bad guys” taking over the power grid of the West Coast and causing blackouts, which lead to turmoil in the major cities, etc. I read the script and told him that if I were to handle it, I’d do a page one rewrite, which meant starting from scratch with the core concept and some of the characters. I pitched him my version of it, which was basically Die Hard with a blacked out Los Angeles. It was my dream to write a Die Hard sequel, so this was the next best thing. He liked my pitch and I was hired for the job. DW: Was writing for TV harder than features? |

KM: It’s different. With television, it’s much faster paced. The deadlines are much harsher. Since Blackout was pre-sold, people were waiting for it to distribute. The studio had a small window to get this done. So I had to write it in two and a half weeks. Again, this was a page one rewrite so we were starting from scratch here. On top of that drastic two and a half week deadline, I was writing a miniseries. A two night event. Four hours. So it’s like writing a movie AND a sequel, as far as pages go. 250 pages in two and a half weeks. Needless to say, I didn’t see my family that much in those couple of weeks. But I got it done in time and they were very happy with that first draft. Despite the deadline, we still had another two drafts beyond that, which is good, because like feature contracts a writer is paid not in lump sum, but by how many drafts you are contracted for. So for television, the deadlines are just harsher. The miniseries hasn’t hit the states yet, but it’s been a Top 20 show overseas.

DW: You’ve had many studio meetings as a writer. What are those like? Reports vary, to say the least.

KM: Writers are often told to expect to walk into a dark room with executives in suits sitting at the end of a long table. That’s BS. It was never like that with me. It’s a dated cliché. I had meetings at Dreamworks, Universal, Sony, Warner Brothers, and Disney. The biggest studios in the world. And none of those meetings were anything like that. The producers and development executives I met with were real people in business casual ware. They were film lovers like me. The mood, despite some obvious nervousness initially on my part, was relaxed and casual. We talked about movies. What we love and don’t love. We talked about how that related to my script that they liked.

That’s what those meetings are all about. They want to know if you’re the real deal or a one hit wonder. They want to know if they’ll like working with you. If you’re collaborative, egotistical, difficult, easy, etc. The best possible advice I can give is to let writers know that before they even market anything to the powers that be, be sure to have a stacked deck. NEVER push your first script, or first notable script, too hard. Move onto the next one. Have three strong scripts before you market anything because the first thing that these people ask, after you’ve talked about the script that got you in there, is, “What else do you have?” If you have nothing else, they usually won’t bother. They’ll shake your hand and say, “Tell us when you have something else to look at.” That’s just the truth. Anomalies exist for sure, but a majority of the time, you need to go in that room with a stacked deck. I can’t say that enough.

But overall, the meetings are more casual than you would think. It really only gets more intense when you’ve established yourself with a couple of hits under your belt, and now have to pitch your take on a big studio movie tent pole flick that you are being considered for. Then it can get more intense because there are big players involved, millions of dollars, and you’re one of many vying for the big job.

DW: How did you become a writer?

KM: The short answer is: “I started to write.” How can you expect to call yourself a writer, or even aspire to be one, without writing? It’s not enough to have ideas. Everyone does. The waiter at your table has ideas. The cashier at the grocery store has ideas. The local dentist has ideas. Who cares? Ideas are nothing. It’s about the writing. It’s about actually sitting down and writing the damn thing. Getting your head out of the clouds and just doing it. Most people can’t commit to that. Most people don’t have the talent or self-discipline to take a great idea and create great stories and characters to go along with it. I loved movies. Since a very early age. I hung out in a video store (remember those?). I later worked at that video store. I watched so many movies. I had ideas. I wrote short stories. I read books. I then learned the screenplay structure by reading all of the books I could find on the subject. Good and bad. I studied movies. And then I just wrote. I moved to Los Angeles with my wife (then fiancé) in 1999. I wrote scripts. I failed. I wrote some more. I embedded myself within the film industry to learn the ins and outs. And eventually I became a produced screenwriter.

DW: Do you miss Hollywood? The work you used to do?

KM: I’d be lying if I said I didn’t. What I don’t miss is the traffic. I don’t miss the impossible real estate prices. I don’t miss the costs. I don’t miss the city life. Here in Wisconsin we live in a great house, great neighborhood, near friends and family. We couldn’t have had this wonderful life in Los Angeles. But I do miss things for sure. I miss my golf cart. I miss the days where I could just hop on cart and drive around the studio lot, seeing a giraffe being lead in between soundstages to my right and passing Steven Spielberg in his own golf cart to my left (Both really happened at the same time). I really do miss that studio life. There was an energy to it.

I was fortunate enough to be able to visit Sony when I flew to Los Angeles to be on set for Blackout. I drove into the VIP gate for a meeting and realized that this was the very booth that I worked at when I was a security guard. I had tears in my eyes. I was finally on the other side of that booth. I had the VIP drive on. I was the one they were calling sir. I couldn’t resist telling the security guard that I used to work in that booth. It was a defining moment in my life, believe it or not. I don’t miss much beyond that studio life. I love where I am now and will always be a flight away from the Hollywood experience when and if duty calls.

DW: You currently write for Quora. What kind of work is that?

KM: Quora is amazing. In a way, it’s therapy for me as a writer. I can’t stress enough how important of a site it is. It’s more than just a mere Question and Answer site. This company is trying to change the game, so to speak. They are trying to be the place where the world’s knowledge is collected. It’s a place where people in the know can share their experience and knowledge. It’s also entertaining and informative for the reader. For me, it’s a chance to give back. I answer questions regarding the film industry, offering information that I would have loved to have had back when I started out. That’s the beauty of Quora. You can go there to learn from the best. And anyone can do it. If you have knowledge and experience to share on nearly any subject, Quora is the place to go. And beyond subject or topics of expertise, you can just go there to share yourself. To share a viewpoint. A perspective.

The best thing about it in my opinion is the community. There’s an actual rule that states, “Be nice.” Users respect each other and if they don’t, they are told to leave. So it’s just a great community overall. Positive. And it truly is the place to go for knowledge. You have vets, NASA employees, professors, law enforcement, athletes, major actors, major directors, scientists, engineers, programmers, etc.; everything and everyone, waiting to answer your questions in details. It’s amazing. Honestly, go there now.

DW: You relocated back to the Midwest to raise your kids. Was it strange leaving Hollywood after a while? Even California?

KM: Yes. It was a culture shock. We were only there for seven years, but when we returned, it truly was a culture shock. Even when we still lived there but returned home for the holidays, driving around Wisconsin in between hometowns of my wife and I was an unreal experience. Seeing all of the nature in between our destinations. Wow. When we moved back, it was just a different culture. Things moved slower, but the traffic was certainly faster. People were more personal, in the best of ways. More smiles. More laughter. More real. And being able to spend less than $200,000 on a nice, new house with a big yard for our boys was a culture shock in its own. What we have now would have been worth at least $2 million in Los Angeles. I would never move back. I’ve had opportunities to do so and didn’t even flinch when turning them down. It’s a wonderful life here in Wisconsin. As most people have hated the winter, after living in Los Angeles with virtually no change of seasons, I never complain. Except the mosquitoes here. We never had those in Los Angeles. I hate the mosquitoes here.

DW: Many say the Midwest and other parts of America are test markets for Hollywood content.

KM: In the end, it’s all about demographics. It’s all about creating four quadrant movies, which means those that both male and female, over and under 25 years old. Or focusing on one particular quadrant. Or a combination. It’s a myth that Hollywood would center on any particular geographic paradigm or trend. All they care about is risk factors. The more quadrants they can market to, the better. The only geographical element is the international market, which is HUGE for studio films. International box office can save a domestic dud, so they’ll never want to alienate a nation like China.

It’s all about the quadrants and how broad of an audience they can reach. This is a generalization, for sure, but it proves to be the majority time and time again. But writers have to, again, find that middle ground and create a hybrid of stories they want to tell, but within the realm of the guidelines and expectations of the film industry.

KM: There have been the good and the bad. Seeing a fourth Indiana Jones in 2008 and being utterly gutted by how terrible it was. That’s the bad that still resonates. Then there are the good moments, which are too plentiful to list here. Moments that engage my excitement and imagination. One of my first memories from my childhood was watching Star Wars in the movie theater when I wasn’t even walking yet. Or seeing Raiders of the Lost Ark when I was maybe four and screaming at the top of my lungs when a snake came out of a skull. Or sitting at the left side of a packed theater during opening weekend of Return of the Jedi and being utterly floored when Vader’s helmet was taken off by Luke. Those are the moments that have stuck with me most. Magic. But perhaps the greatest and most proud moments are when I look to my right and left in a movie theater and see my two boys sitting beside me, wide-eyed at what they are watching on that big screen as they stuff their faces with popcorn. That’s the true magic of cinema for me. It’s like I’m reborn again. Reliving those first memories.

DW: Thanks so much for your time, Ken, and see you at the Writer’s Institute spring conference in Madison April 4!

KM: I’m looking forward to the Writer’s Institute for sure. Thanks so much for having me. It’s been a pleasure.

Clip: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=56fngopihOo

Dave Watson is the Editor of Movies Matter. He lives in Madison, WI.

DW: You’ve had many studio meetings as a writer. What are those like? Reports vary, to say the least.

KM: Writers are often told to expect to walk into a dark room with executives in suits sitting at the end of a long table. That’s BS. It was never like that with me. It’s a dated cliché. I had meetings at Dreamworks, Universal, Sony, Warner Brothers, and Disney. The biggest studios in the world. And none of those meetings were anything like that. The producers and development executives I met with were real people in business casual ware. They were film lovers like me. The mood, despite some obvious nervousness initially on my part, was relaxed and casual. We talked about movies. What we love and don’t love. We talked about how that related to my script that they liked.

That’s what those meetings are all about. They want to know if you’re the real deal or a one hit wonder. They want to know if they’ll like working with you. If you’re collaborative, egotistical, difficult, easy, etc. The best possible advice I can give is to let writers know that before they even market anything to the powers that be, be sure to have a stacked deck. NEVER push your first script, or first notable script, too hard. Move onto the next one. Have three strong scripts before you market anything because the first thing that these people ask, after you’ve talked about the script that got you in there, is, “What else do you have?” If you have nothing else, they usually won’t bother. They’ll shake your hand and say, “Tell us when you have something else to look at.” That’s just the truth. Anomalies exist for sure, but a majority of the time, you need to go in that room with a stacked deck. I can’t say that enough.

But overall, the meetings are more casual than you would think. It really only gets more intense when you’ve established yourself with a couple of hits under your belt, and now have to pitch your take on a big studio movie tent pole flick that you are being considered for. Then it can get more intense because there are big players involved, millions of dollars, and you’re one of many vying for the big job.

DW: How did you become a writer?

KM: The short answer is: “I started to write.” How can you expect to call yourself a writer, or even aspire to be one, without writing? It’s not enough to have ideas. Everyone does. The waiter at your table has ideas. The cashier at the grocery store has ideas. The local dentist has ideas. Who cares? Ideas are nothing. It’s about the writing. It’s about actually sitting down and writing the damn thing. Getting your head out of the clouds and just doing it. Most people can’t commit to that. Most people don’t have the talent or self-discipline to take a great idea and create great stories and characters to go along with it. I loved movies. Since a very early age. I hung out in a video store (remember those?). I later worked at that video store. I watched so many movies. I had ideas. I wrote short stories. I read books. I then learned the screenplay structure by reading all of the books I could find on the subject. Good and bad. I studied movies. And then I just wrote. I moved to Los Angeles with my wife (then fiancé) in 1999. I wrote scripts. I failed. I wrote some more. I embedded myself within the film industry to learn the ins and outs. And eventually I became a produced screenwriter.

DW: Do you miss Hollywood? The work you used to do?

KM: I’d be lying if I said I didn’t. What I don’t miss is the traffic. I don’t miss the impossible real estate prices. I don’t miss the costs. I don’t miss the city life. Here in Wisconsin we live in a great house, great neighborhood, near friends and family. We couldn’t have had this wonderful life in Los Angeles. But I do miss things for sure. I miss my golf cart. I miss the days where I could just hop on cart and drive around the studio lot, seeing a giraffe being lead in between soundstages to my right and passing Steven Spielberg in his own golf cart to my left (Both really happened at the same time). I really do miss that studio life. There was an energy to it.

I was fortunate enough to be able to visit Sony when I flew to Los Angeles to be on set for Blackout. I drove into the VIP gate for a meeting and realized that this was the very booth that I worked at when I was a security guard. I had tears in my eyes. I was finally on the other side of that booth. I had the VIP drive on. I was the one they were calling sir. I couldn’t resist telling the security guard that I used to work in that booth. It was a defining moment in my life, believe it or not. I don’t miss much beyond that studio life. I love where I am now and will always be a flight away from the Hollywood experience when and if duty calls.

DW: You currently write for Quora. What kind of work is that?

KM: Quora is amazing. In a way, it’s therapy for me as a writer. I can’t stress enough how important of a site it is. It’s more than just a mere Question and Answer site. This company is trying to change the game, so to speak. They are trying to be the place where the world’s knowledge is collected. It’s a place where people in the know can share their experience and knowledge. It’s also entertaining and informative for the reader. For me, it’s a chance to give back. I answer questions regarding the film industry, offering information that I would have loved to have had back when I started out. That’s the beauty of Quora. You can go there to learn from the best. And anyone can do it. If you have knowledge and experience to share on nearly any subject, Quora is the place to go. And beyond subject or topics of expertise, you can just go there to share yourself. To share a viewpoint. A perspective.

The best thing about it in my opinion is the community. There’s an actual rule that states, “Be nice.” Users respect each other and if they don’t, they are told to leave. So it’s just a great community overall. Positive. And it truly is the place to go for knowledge. You have vets, NASA employees, professors, law enforcement, athletes, major actors, major directors, scientists, engineers, programmers, etc.; everything and everyone, waiting to answer your questions in details. It’s amazing. Honestly, go there now.

DW: You relocated back to the Midwest to raise your kids. Was it strange leaving Hollywood after a while? Even California?

KM: Yes. It was a culture shock. We were only there for seven years, but when we returned, it truly was a culture shock. Even when we still lived there but returned home for the holidays, driving around Wisconsin in between hometowns of my wife and I was an unreal experience. Seeing all of the nature in between our destinations. Wow. When we moved back, it was just a different culture. Things moved slower, but the traffic was certainly faster. People were more personal, in the best of ways. More smiles. More laughter. More real. And being able to spend less than $200,000 on a nice, new house with a big yard for our boys was a culture shock in its own. What we have now would have been worth at least $2 million in Los Angeles. I would never move back. I’ve had opportunities to do so and didn’t even flinch when turning them down. It’s a wonderful life here in Wisconsin. As most people have hated the winter, after living in Los Angeles with virtually no change of seasons, I never complain. Except the mosquitoes here. We never had those in Los Angeles. I hate the mosquitoes here.

DW: Many say the Midwest and other parts of America are test markets for Hollywood content.

KM: In the end, it’s all about demographics. It’s all about creating four quadrant movies, which means those that both male and female, over and under 25 years old. Or focusing on one particular quadrant. Or a combination. It’s a myth that Hollywood would center on any particular geographic paradigm or trend. All they care about is risk factors. The more quadrants they can market to, the better. The only geographical element is the international market, which is HUGE for studio films. International box office can save a domestic dud, so they’ll never want to alienate a nation like China.

It’s all about the quadrants and how broad of an audience they can reach. This is a generalization, for sure, but it proves to be the majority time and time again. But writers have to, again, find that middle ground and create a hybrid of stories they want to tell, but within the realm of the guidelines and expectations of the film industry.

KM: There have been the good and the bad. Seeing a fourth Indiana Jones in 2008 and being utterly gutted by how terrible it was. That’s the bad that still resonates. Then there are the good moments, which are too plentiful to list here. Moments that engage my excitement and imagination. One of my first memories from my childhood was watching Star Wars in the movie theater when I wasn’t even walking yet. Or seeing Raiders of the Lost Ark when I was maybe four and screaming at the top of my lungs when a snake came out of a skull. Or sitting at the left side of a packed theater during opening weekend of Return of the Jedi and being utterly floored when Vader’s helmet was taken off by Luke. Those are the moments that have stuck with me most. Magic. But perhaps the greatest and most proud moments are when I look to my right and left in a movie theater and see my two boys sitting beside me, wide-eyed at what they are watching on that big screen as they stuff their faces with popcorn. That’s the true magic of cinema for me. It’s like I’m reborn again. Reliving those first memories.

DW: Thanks so much for your time, Ken, and see you at the Writer’s Institute spring conference in Madison April 4!

KM: I’m looking forward to the Writer’s Institute for sure. Thanks so much for having me. It’s been a pleasure.

Clip: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=56fngopihOo

Dave Watson is the Editor of Movies Matter. He lives in Madison, WI.