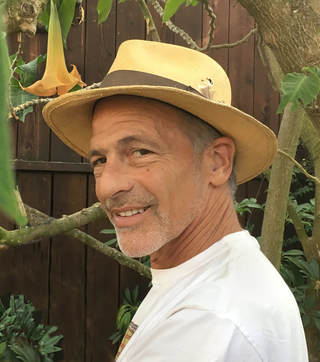

DAVID SONNENSCHEIN is the author of SOUND DESIGN: THE EXPRESSIVE POWER OF MUSIC, VOICE AND SOUND EFFECTS IN CINEMA, from Michael Wiese Productions. David pulls from many life threads such as neuroscience research, as a music performer and composer of classical, jazz, world, and music therapy, film and games (director, producer, writer) and as an educator, lecturing and giving workshops in fifteen countries, with pre-schools through graduate schools and professionals. His love for science, art, health and communication are currently focused in his company iQsonics producing music games for brain health, including Sing and Speak 4 Kids, an online interactive program to support autism and speech delay in children. We spoke recently about the use of sound in film, how it triggers and interacts with neuroscience, and the breakthrough cinematic moment.

Visit iQsonics.com and SoundDesignForPros.com, contact [email protected].

Dave Watson: First, congratulations on the book. How did it come about?

David Sonnenschein: I was a sound designer for many years with a background as a musician, filmmaker and neuroscience. I was living in Brazil in 1998 and was invited to teach sound design at the film school in Havana, Cuba, and was looking around for texts on this subject which I couldn’t find. From this opportunity to teach a two-week class on sound design. I felt like I’d created an outline for a book. I submitted to a couple publishers and was immediately accepted by Michael Wiese Productions. It was a two-year process to put together the book.

DW: To a worldwide tour.

DS: This led to numerous university and corporate teaching gigs over the last twenty years or so along with many tours internationally, to about fifteen countries lecturing at conferences, workshops. The book itself has been translated into four languages: Chinese, Japanese, Vietnamese, and Korean.

DW: Asian languages.

DS: Yes, the European market is mostly in English.

DW: Were there any surprises while writing the book?

DS: Not really--I outlined the book from my research, which includes thirty reference books. Probably the biggest surprises were from interviews with top sound designers. They gave many insights I didn’t foresee.

DW: You talk about the sound map. How crucial is this? What is it exactly?

DS: Sound mapping isn’t common industry jargon, but something I created that’s very useful for designing sound based on a story. It’s the story map, plotting of the film along its storyline, a timeline of what happens when. Specifically, I created this for sound design, but can also be used for production design, casting, or music, various areas. What we’re doing is mapping is the authentic curve of the story. The map is created by defining dramatic conflict of the story, the protagonist and antagonist combining what I call “bi-polarities” such as good vs. evil, life vs. death etc. Stories can be mapped along a timeline, scene-by-scene and dramatic shifts, for example moments when the good guy is winning, or other times when it looks like all is lost. We’re using the map as a guideline for sound bi-polarities. By bi-polarities I mean, for example, loud and soft, sudden attack versus a gradual attack. These sound qualities have to be measurable and modified to match the sound bi-polarities with the dramatic bi-polarities, and this is a way of codifying the dramatic actions. You’ll watch that’s what’s happened in many, many films even if they didn’t use this particular sound mapping tool.

DW: When does the sound designer enter the filmmaking process. Some say, “Oh they add that in post,” what I’ve heard.

DS: The sound mapping can actually be used as a blueprint for the whole team to work in synch so that we all have a common reference point. The director, the editor, way before shooting. Actually as a film director and consultant to others, I encourage others to do the sound mapping early in the beginning so you see what could be boring or over-stimulating without an emotional release. The sound generally needs a very fluid process of coming and going for the elements. Once you’ve got that, the whole team, the director, the cinematographer, the editor, the costumer, they can all use the sound map because we are all telling the same story.

The music composer ideally collaborates with the director and sound designer before you start cutting picture so they can all work together in the creative editing and storytelling process.

DW: And experienced. The sound is a big part of how the film is experienced. The sound almost enwraps the audience. One of the reasons I’m a film fan is it is such a consummate experienced.

DS: Right, how the film is seen, heard, and felt.

DW: Sound appears taken for granted to many audiences. Would you say it's one of the most subconscious parts of filmmaking? You mention meditation at one point in your book.

DS: It’s not just the subconscious parts of filmmaking, but also the experience as human beings. We are not so aware of sound in our environments, compared to the images. A dog for instance might be more aware of sound, an eagle of visuals; different species have different neurologies and perceptions. Our ears transform sounds to our nervous system and our older limbic regions of our brains before it arrives in the frontal auditory cortexes. What this means is that we react to sound first on an emotional basis rather than a cognitive one, compared to visuals that go directly to the cognitive visual cortex of the brain. That’s why music is so powerful. I call sound designers the ninjas of filmmaking because we shift the audience’s feelings without their conscious awareness.

DW: I’m thinking of Blade Runner 2049, when he’s in the bowels of the machinery and he’s going toward the oven, we think we know what he’ll find when he unfurls the wrapping, and the sound really ratchets up.

DS: Yes, we enjoy it on a visceral level that stimulates our visual experience and I like to play with that area of sound.

DW: You also discuss different forms of speech. I re-watched The Doors recently with overlapping sounds where sounds cut in and out of each other. How hard is this to do well?

DS: It starts with the idea that you “see a dog, then hear a dog,” and so on. We have an expectation that that is normal. When you play with that reality it creates cognitive dissonance. With The Doors the director is distorting the reality with sound, you can take it out-of-sync. sometimes makes dialogue unintelligible. David Lynch did something interesting with Twin Peaks. He had the actors say their lines in reverse, then he turned around and played it backwards, so it worked, but the breathing and other sounds were very odd. Another example is The Conversation, Coppola’s film is all about listening to dialogue that is not quite clear, mixing and matching sounds as the main character unravels a mystery. Sometimes you muffle it and you can’t hear it well, then you add sounds on top or break them up; that technique can frustrate the audience. If you’re going to do that, it has to have a clear purpose in the storyline.

DW: Same with Brian De Palma’s Blowout.

DS: Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind is another example. Much of it’s taken from the same location. They're distinguishing which is which by the use of reverb by dialogue that happened in the past. So that’s another manipulation of sound to indicate different states of conscience.

DW: What's one of the best sound-designed films you've experienced?

DS: Eternal Sunshine has an extraordinary storyline through the sound because it’s shifting in consciousness and aiding in the character’s and audience’s confusion. Then there are the revelations, who’s aware of what. Fight Club is another one also with insights and internal sounds related to the characters. There are some classics like Raging Bull; I had the fortune to interview Frank Warner, who also did Close Encounters. He had a team and he assigned each member of his team to work on and oversee an element of the sound. One person was in charge of the punches, so each fight didn’t sound the same and it was like a musical composition. Another was just in charge of the crowd sounds. Martin Scorsese told Frank that he didn’t want any musical score and that the only music we would hear would be coming out of the radio. So the sound design elements by themselves functioned like a typical musical score, carrying the emotional context of the scenes.

DW: As long as it was clear to the audience.

DS: Yes. It empowered the sound designer to do extraordinary things and he invested a lot of time into that composition. Another example is Ben Burtt who worked on all the Star Wars and Indiana Jones films. I loved how he discovered sounds. For E.T. he recorded many different animal and human sounds and structured them for E.T.’s language, which evolved from grunts into words we could eventually understand.

DW: They are integral to the organic and consummate experience of the film.

DS: Absolutely. How did he make the sound of the light saber? It was a high-tension wire. He tapped the wire, creating a sound wave traveling the length of the wire up and down and recorded that sound. With Darth Vader, everyone in the world recognizes Darth Vader’s breathing which is in fact a scuba breathing apparatus. I call it media specific referential listening. Some sounds like the Apple computer booting up or an ambulance siren, throughout our culture we hear sounds and they evoke images for us.

DW: I was in a Buddhist temple in Japan when our tour guide showed us the samurai gear and helmet, which many compare to Nazi helmets, and our Japanese guide said it looked like Darth Vader, then he turned to us and emulated the breathing sound!

DW: What’s next for you?

DS: I’ve worked in the interactive medium as a consultant for large games like Mass Effect and been creating my own games for audio and music-centric. We created a game called “Sing and Speak 4 Kids” that uses image and sound to help children with autism and speech delays learn through speech and song. It utilizes my scientific and music background and serves a needy population. We’ve launched a pilot trial and will have a commercial release in the next year. I’m really excited to make change in the world and believe my book, classes and workshops have served many people to make more interesting films. But the excitement in my life is to do something that’s never been done before and changing people’s lives is extremely rewarding. You can view my website iQsonics.com for more info. What’s next for me is in the areas of Augmented Reality and A.I.

DW: Finally, what is your favorite cinematic moment? One that inspires you to this day?

DS: I saw The Wizard of Oz at an early age and every year I watched it in black and white growing up. When I was ten, I was invited to see it in the theater and the scene when the house lands, Dorothy wakes up and opens the door and sees all the color, it is so ingrained in our conscience. I was in shock. That scene plays to our deepest subconscious and that moment when it turned into color was so dramatic. I directed a feature film in Portuguese in 1988 when I was living in Brazil. Super Xuxa contra Baixo Astral (Super Xuxa against the Bad Vibes). This film’s main character Xuxa was modeled after Dorothy, including as her dog is kidnapped. Now thirty years later, fans of that film have interviewed everyone involved in that film and have been posting these interviews with clips from the film. They say it’s their favorite film of all time. So we’ve received and created a lot of inspiration over the years.

Clip: The Wizard of Oz