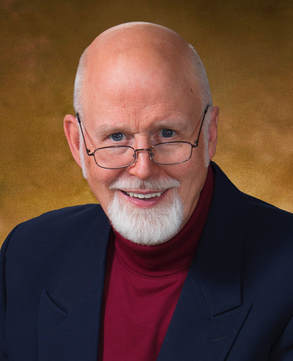

Stan Williams is an award-winning veteran filmmaker of hundreds of corporate and non-profit documentaries. He has worked on over a dozen major Hollywood motion pictures as a screenplay and script doctor, and seen many of his projects distributed around the world. He is the author of THE MORAL PREMISE: HARNESSING VIRTUE AND VICE FOR BOX OFFICE SUCCESS and holds a B.A. in Physics, and a Ph.D. in Narrative Theory. He is the writer-director behind the forthcoming romantic comedy ANNALIESE! ANNALIESE! We spoke recently about audiences as moral agents, what Socrates and Seinfeld have in common, and his favorite cinematic moment from a destined classic.